A French version of the SAIL Magazine article I wrote as a 17-year-old resurfaced this week. It was published nearly a half century ago about a voyage I made from Florida to New England in a small wooden boat named Icarus. Courtesy: Thibaud Deves

I am not one who has ever been comfortable waiting around for things to happen.

Today I am in Langkawi, Malaysia waiting for parts to repair the navigational electronics aboard Flying Fish before I set sail across the Indian Ocean.

Forty-seven years ago, I was also waiting. I was counting off the days until high school ended so I could set sail along the eastern seaboard of the United States in an 18-foot plywood sailboat I owned named Icarus.

My brother Bob joined me aboard Flying Fish on the first leg of this circumnavigation. He was also aboard Icarus for the first leg of that voyage. In 1973, Bob was already in college following a sensible path in life studying marine biology, working on a Chinese vegetable farm, and cultivating a crop of high-potency marijuana. He took time off from his busy schedule and we had a delightful passage together. Some days we sailed offshore, on other days we cruised through the Intracoastal Waterway. At Little River, South Carolina Bob went back to Tallahassee for graduate school (and harvest season) while I took a job as a fish gutter on an assembly line with spirited Low-Country black women who sang while they worked and taught me a few words of Gullah. I was broke and happy, and had all of the pan-fried croaker I would ever want to eat.

It was a notable summer. Secretariat had just become the first Triple Crown winner in 25 years. Former White House counsel John Dean began his testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee. The U.S. bombing of Cambodia ended after 12 years of combat activity in Southeast Asia. But then, like now, I felt insulated from world events. Aboard Icarus, I was lost in the fog–both figuratively and literally.

By mid-summer I was alone on Icarus, transiting Delaware Bay from the Chesapeake to New Jersey. I had no navigational gear onboard and I encountered a fog bank. I am a South Florida boy, born and raised. I had never experienced fog. It was a novelty. I could see the air move when I blew it out of my mouth. But couldn’t see anything else. I could certainly hear things, though. The booming fog horns of ships passing me unseen at close quarters echoed out of the gray nothingness. My intention was to sail toward Cape May, New Jersey while estimating my location by dead-reckoning speed, direction, and time. My charts showed buoys with horns and bells, but nothing made sense to me. I remember the day becoming late. I should have made landfall by mid-afternoon. It was transitioning into night. I’ll turn due north, I thought, and that way I can’t miss the New Jersey shoreline of Delaware Bay. I sailed on through the night. There was no shoreline. Just before daybreak the fog lifted and I finally saw some lights. Land ho? Unfortunately, no.

The lights were from commercial fishing boats trawling the Continental Shelf well offshore of New Jersey. It was calm. I thought I was still in the bay. Instead, I was 35 miles out at sea. I pulled alongside a large trawler and shouted out to a mate on deck, “Where am I?” Soon there was a cluster of crewmen and they tossed me a line and lowered a ladder. Icarus tugged at the end the line like a toy poodle on a leash. “You look like you need food and a bunk,” one of the crew said to me. I was escorted to the captain’s mess for breakfast. The captain walked in, wiped sleep from his eyes, raised a fork to his mouth, then set it it down and looked at me. “Who the hell are you?” he roared. I’m from Icarus, I replied meekly. My boat is tied on rope behind your trawler.

The captain could have called the U.S. Coast Guard and ended the voyage of Icarus at that moment. Instead, after some intense interrogation, he said he would tow Icarus within sight of land and then release the tow line once he was sure I wasn’t going to get lost again. This memory is from so long ago now… but I think I remember seeing the captain’s face soften a little. Maybe it was my youthful naïveté, or maybe he saw something in my face that reminded him of himself. He let loose the tow when I was in sight of the amusement park of Atlantic City. Once again I was alone under sail.

How exciting it was to sail Icarus past the Statue of Liberty, along the shoreline of New York City, under the Brooklyn Bridge, through the Hell Gate passage, and into Long Island Sound. I was full of confidence (somehow forgetting about being lost at sea just days earlier). I was Master and Commander of my little ship–and then I ran Icarus onto a rock in the Stamford, Connecticut harbor and put a hole the size of a basketball through her hull.

I was was sinking. I careened Icarus onto a beach and remembered that a year or two earlier I had crewed on a sailboat race from Florida to Jamaica with Mr. Morgan Ames, Commodore of the Stamford Yacht Club. Help from his club was immediately on hand to haul Icarus out of the water. With his instruction (and checkbook) a crew, including his son, immediately began the necessary repairs. That evening Commodore Ames welcomed me into his magnificent Stamford home. “You’ll stay here,” he said, “and we’ll get you some clothing.” At dinner he introduced me to his family. Then a girl entered the room and he said, “And this is my daughter Bambi.” I nearly swallowed my tongue. I was 17 years old, had been alone on the ocean for weeks, and she was very pretty. I was paralyzed. My mouth finally moved. “B-B-Bambi?” I stammered, “Like the baby deer?”

We were the same age. Bambi showed me around Stamford, introducing me to her friends. My selective memory 47 years later remembers her flaxen hair blowing in the summer breeze. I was enchanted. I had dreams of joining the yacht club, of wearing freshly pressed shirts and a navy blue blazer, maybe even attending a debutante ball! In reality, I was just a wild Florida boy who had suddenly turned up on the Ames family doorstep, dirty, broke, and aboard a homemade boat with a hole in it. Mrs. Ames was having none of it. After a few days she took me aside and I remember her words to me as if they were spoken yesterday. With perfect New England elocution she said, “You should know, Jeffrey, that Bambi already has a beau.”

In quick order, Icarus was repaired and I was sailing again. I will always be grateful to the Ames family for their kindness and generosity, and for the life lessons they imparted upon my young wandering soul. Clearly, I had flown too close to the sun.

At the end of that magical summer I found myself in the storied harbor of Newport, Rhode Island. I put a cardboard sign on Icarus that read: “Send A Kid To College, Buy This Boat.” Somebody did, and all too quickly. Within weeks I was enrolled at the University of Florida. I tried to focus on a formal education but I realized that I was waiting again. Waiting for the next opportunity to set sail.

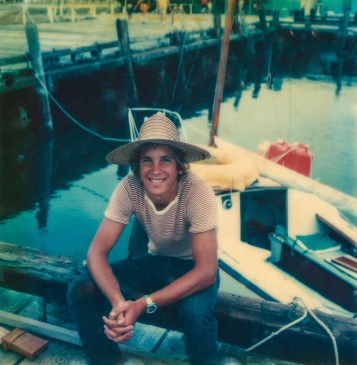

As a boy sailor I was given a long lead to chase my dreams. Here I pose with with 18-foot Icarus during a teenage sailing adventure from Ft. Lauderdale, FL to Newport, RI

NOTE: On passages when I have no cell or WiFi signal, I activate a satellite tracking link that shows my daily position, current weather, and includes a few personal thoughts from the daily log of Flying Fish. I will not be able to respond to messages via satellite but I love the idea that you are sailing along with me. If you would like to follow the daily progress of Flying Fish into Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean via satellite you can click this link: https://forecast.predictwind.com/tracking/display/Flyingfish

Please subscribe at the bottom of this page so that you don’t miss a new update, and consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy following the voyage of Flying Fish.

To see where Flying Fish has sailed since leaving Key West in 2017, click here: https://cruisersat.net/track/Flying%20Fish

Instagram: FlyingFishSail

Text and Photography © Jeffrey Cardenas 2020