Flying Fish anchored against a backdrop of blooming oleander in the environmental preserve of Turkey’s Skopea Limani. Photograph: © Jeffrey Cardenas

Beautiful anchorages seduce me. Turkey’s Skopea Limani is one of those places: the bay is protected from the meltemi winds, it is an environmentally protected area (SEPA) with clear turquoise water, and it is rich in archeological heritage. But before I knew of any of those attributes though, Skopea Limani had me at oleander…

It is a good year for oleander in the Eastern Mediterranean. Viewed from offshore aboard Flying Fish, clusters of oleander blossoms paint the landscape of this arid shoreline. The plant beckons like a Siren with pink flowers and the fragrance of a fine Turkish rosé. Oleander is also considered one of the most poisonous plants in the world.

All parts of this beautiful shrub contain poison–several types of poison. According to the American Poison Control Center, the two most potent toxins in the plant are oleandrin and neriine, known for their powerful effect on the heart and brain. Ingestion of oleander can cause nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and internal bleeding. The effect on the central nervous system may include tremors, seizures, and collapse. The poison of oleander is so strong that a single leaf can kill a person.

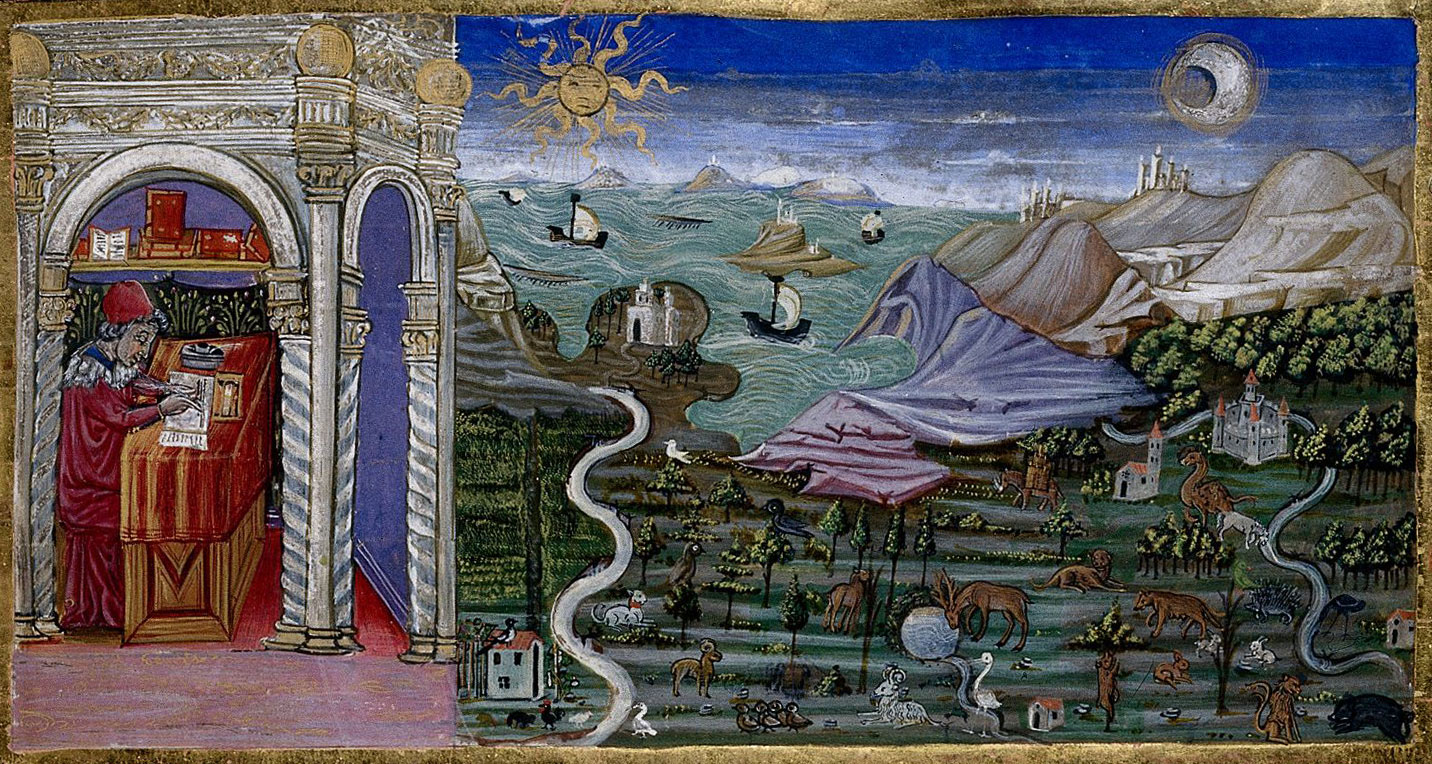

Pliny the Elder, who wrote the epic 37-volume treatise Naturalis Historia in AD 77, investigated natural and geographic phenomena in the Mediterranean. Writing of oleander he said it “…grows in sea-bordering places & in places near rivers. But ye flower and the leaves have a power destructive of dogs & of Asses & of Mules & and of most four-footed living creatures.” But it wasn’t all bad news; Pliny added that oleander was an effective antidote to venomous snakebites if mixed with other herbs.

Miniature by Andrea da Firenze from an edition of Naturalis Historia by Pliny the Elder, c. 1457–58, showing Pliny writing in his study, with landscape and animals. British Library —Public Domain.

It was long considered that oleander could even poison a person who simply eats honey made by bees that have digested oleander nectar. Pliny describes a region in Turkey where bees pollinated poisonous flowers and that toxic honey was left as a poisonous trap for an invading army. King Mithridates also used the honey as a deliberate poison when Pompey’s army attacked the Heptakometes in Asia Minor in 69 BC. The Roman soldiers became delirious and nauseated after being tricked into eating the toxic honey, at which point Mithridates’s army attacked. More recent scholars, however, contend that the flowers have been apparently mis-translated. Oleander flowers are nectarless and therefore cannot transmit any toxins via nectar. According to a team of Turkish doctors who in 2009 wrote the wonderfully titled report Mad honey sex: therapeutic misadventures from an ancient biological weapon, the actual flower referenced by Pliny was probably a variety of rhododendron, which is still used in Turkey to produce a type of hallucinogenic honey.

Oleander also has its own record of hallucinogenic qualities. A 2014 article in the medical journal Perspectives in Biology and Medicine suggests that oleander was the substance used to induce hallucinations in the Pythia, the female priestesses of Apollo, also known as the Oracle of Delphi.

A 19th century vision of how the Pythia might have looked intoxicated by hallucinogenics. Priestess of Delphi by John Collier, 1891 —Public Domain

According to this theory, the symptoms of the Pythia’s trances (enthusiasmos) correspond to either inhaling the smoke or chewing small amounts of oleander leaves. And in his book Enquiries into Plants circa 300 BC, Theophrastus described a shrub he called onotheras, which modern editors render as oleander. When administered in wine, oleander was said to “make the temper gentler and more cheerful.”

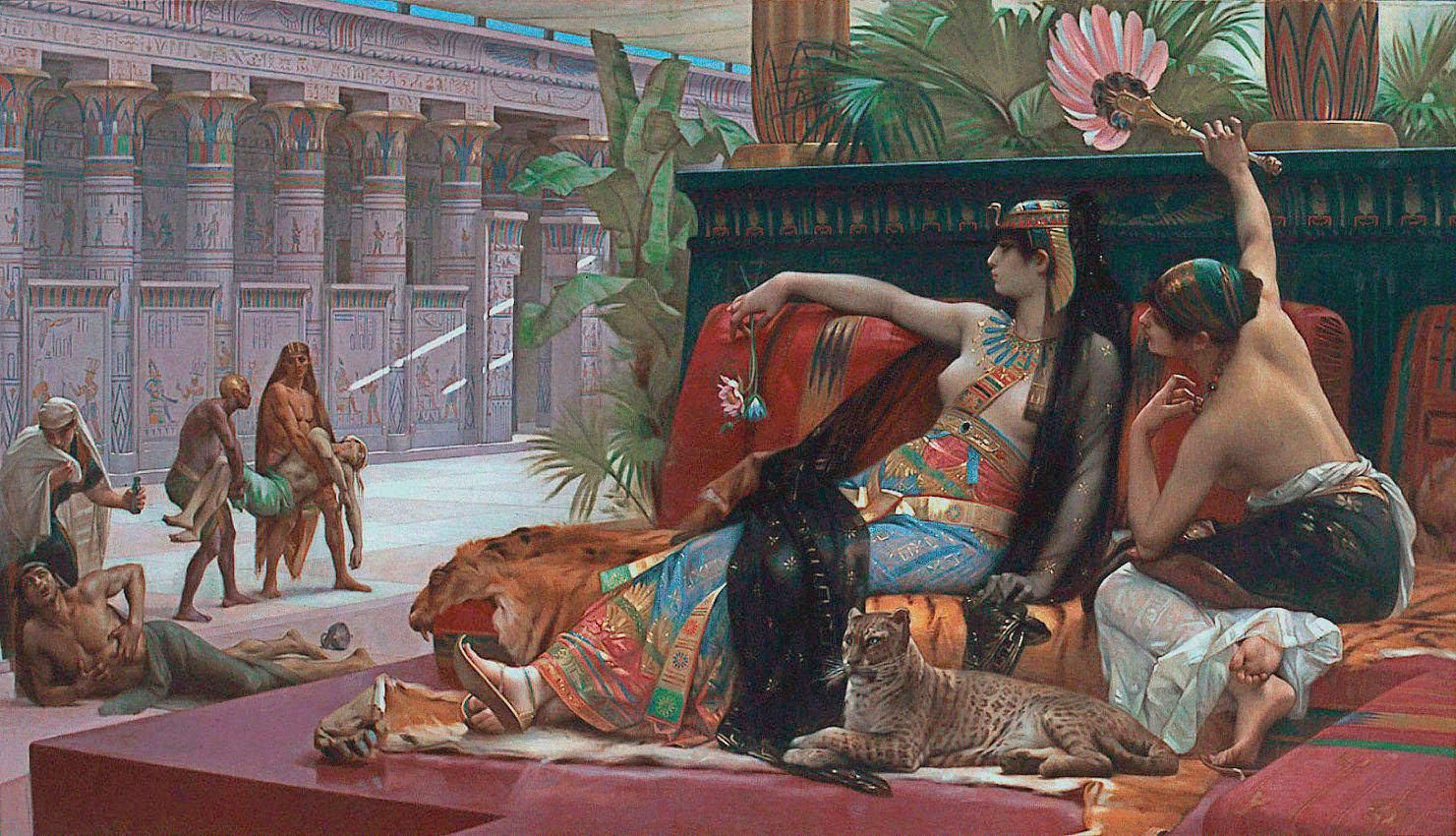

Cleopatra was fascinated with oleander. According to her legend she tested its effects on her servants when she was researching the best vehicle to commit suicide as Octavian descended upon ancient Alexandria. When Cleopatra saw the horrific symptoms of oleander (vomiting, facial contortions, severe convulsions), she opted for a less violent way to die. (Interesting footnote: Pulitzer Prize winning author Stacy Schiff suggests that it was also highly unlikely that Cleopatra killed herself with the bite of a poisonous snake, as has been suggested for thousands of years.)

So what does the Mediterranean history of oleander have to do with sailing? Nothing and everything. The voyage of Flying Fish is one driven by curiosity. I am attracted to the aesthetics of nature and how nature not only affects me but also those who sailed these waters before me. That said, the research reminds me that I shouldn’t put oleander leaves in my salad, or mix it with my wine. I would never have guessed that just kneeling on some fallen leaves while I crouched down to make a photograph would set my skin on fire. My antidote was far less complicated than in the time of Pliny the Elder–I just popped a double dose of Benadryl and settled in for some nice dreams.

###

Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners is an 1887 painting by the French artist Alexandre Cabanel showing Cleopatra observing the effects of poisons, including oleander, on prisoners condemned to death. —Public Domain

- REFERENCES

- International Oleander Society: Information on Oleander Toxicity

- Wikipedia.org: Nerium

- Pliny the Elder: Natural History

- Stacy Schiff: Cleopatra

Please subscribe at the bottom of this page so that you don’t miss a new update, and consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy following the voyage of Flying Fish. Readers encourage me to continue writing.

If you would like to follow the daily progress of Flying Fish into the Mediterranean, and onward, you can click this link: https://forecast.predictwind.com/tracking/display/Flyingfish

To see where Flying Fish has sailed since leaving Key West in 2017, click here: https://cruisersat.net/track/Flying%20Fish

Instagram: FlyingFishSail

Facebook: Jeffrey Cardenas

Text and Photography © Jeffrey Cardenas 2020

Another great, informative article. Many thanks Jeffrey!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks gsh330! It is fascinating to discover a world completely new to me.

LikeLike

So interesting Jeff! I knew that oleander was poisonous but you put it so eloquently! I do love these flowers! I have them in my yard. All the pink beauty!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oleander is gorgeous, and I knew it made you sick, but until I began researching it I didn’t realize it had such a fascinating–and fatal–history. Thank you for commenting Leanne.

LikeLike

Fascinating. Love reading about your curiosities, Jeff. Thanks for the accompanying research references so we can read more as desired.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is wonderful to be sailing in an area where I can access online research. There were times on this voyage in the Pacific and in Indonesia where I couldn’t connect for weeks. The travel fires up my curiosity.

LikeLike

Very interesting, as always. I’ve wanted to plant Oleander in the yard for years. Leslie would have none of it because she assumed the dog would eat the leaves – he is a little nutty and puts anything and everything in his mouth still at 10 years old. We’ll just have to admire it elsewhere. Happy sails!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Ruben. I’ll still put anything in my mouth and I’m a little bit older than your dog.

I always appreciate hearing from you. Warm regards to you and your family.

LikeLike

You had me at hallucinogenic. And honey. So I just boiled down some oleander leaves from the side yard into a nice tea. I’ll get back with ya…

LikeLiked by 1 person

With everything else going on in the world God help us if we get invaded by a swarm of hallucinogenic bees…

LikeLike

An interesting report from an area a lot older than ours! Meanwhile we are all still in sailing lockdown as far as heading to warmer climes are concerned. A very different cruising season in the south pacific so good you took action to isolate in such an historic qth. Thanks from patricia and david

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is so wonderful to hear from you Patricia.

From an outsider’s perspective it seems like New Zealand has done everything right to protect its citizens from the virus.

Stay healthy and happy, and I remain grateful to you and David for all that you did to help me on my passage through your part of the world.

LikeLike