Amid the rubble of ancient Knidos there is an omnipresent ethos of the goddess Aphrodite. Photograph: © Jeffrey Cardenas

Sailing along the Turkish Mediterranean coast is a continual voyage through antiquity. Ruins rise from the sea at nearly every headland to meet the mariner. At Knidos, there are the remains of a temple dedicated to Aphrodite and among its detritus is the essence of a goddess. In the history of classical art the sculpture of Aphrodite of Knidos may be the first example–it is certainly the most celebrated–of a woman portrayed entirely nude. I quickly furl the mainsail aboard Flying Fish and go ashore to ancient Knidos.

The Temple of Aphrodite Euploia (Aphrodite, Sea Goddess of Safe Voyages) has drawn sailors to this shoreline for more than 2,300 years. Knidos became prominent in the ancient world for hosting this sublimely erotic statue of the goddess, sculpted by Praxiteles in 365 BC. The structure housing it, now in ruins, was a circular Doric temple surrounded with colonnades. The goddess graced the center of the temple; her statue made of Parian marble. Aphrodite teased with a shy smile. Nothing hides her beauty other than a furtive hand veiling her modesty. The statue of Aphrodite was not traditionally placed in the end of the hall of the temple’s cella. Instead, it was sited in the middle of the circular foundation making it possible for visitors to admire the statue from all angles. The statue of the goddess was said to have a particularly attractive backside.

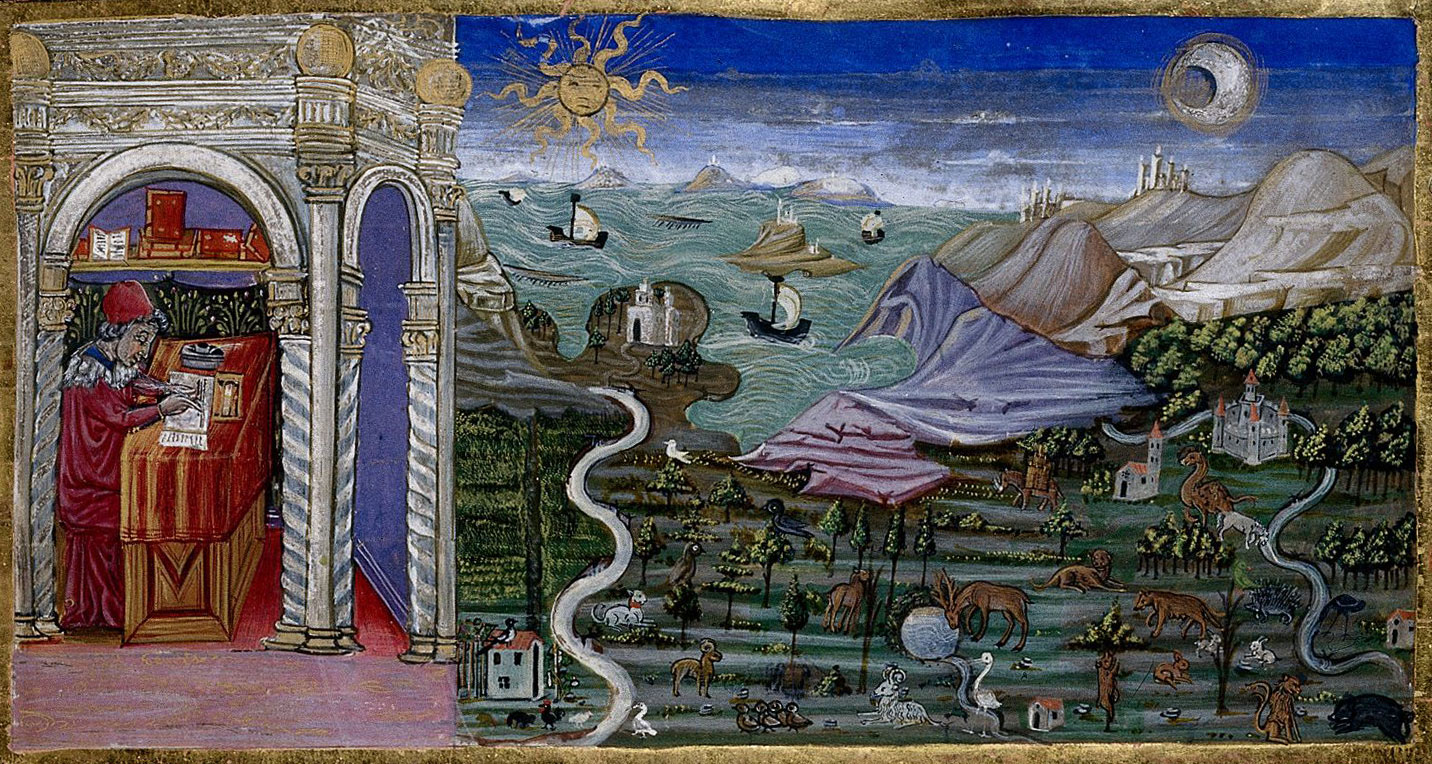

Aphrodite of Cnidus, a Roman marble copy of the Greek statue by Praxiteles, c. 350 BC, Vatican Museum. –Public Domain

Knidos, or Cnidus in the 4th century BC, was a Hellenic city in southwestern Asia Minor, now on the Datça peninsula in modern-day Turkey. Because of this strategic geographical location the Knidians acquired considerable wealth in trade and commerce. The city was less than a mile long, and the entire area remains covered with architectural artifacts. In addition to the spectacular Corinthian temples on Knidos there was an acropolis, an odeum, and numerous marbled terraces and theaters. The ancient city was said to even have its own medical school.

Knidos is now a ruin and deserted, except for tourists and mariners who come to pay homage to its heritage. In ancient times, however, it was at the center of the world on the trade routes from Alexandria to Athens. Its harbor sheltered sailors from the violent meltemi winds. Scorched and bleached by the sun and surrounded by the turquoise Mediterranean Sea, Knidos is both harsh and idyllic. The walls of the ancient harbor still stand. Fragments of column and cornice and terracotta are scattered in the rocks and wind-sculpted bushes of the maquis. In summer the ground releases the fragrance of wild sage growing among shards of ancient earthenware.

Knidos remained somewhat isolated from the western world until The Society of Dilettanti, a group of British noblemen and scholars (and, ultimately, plunderers) sponsoring the study of ancient Greek and Roman art sent an exploratory mission there in 1812. Additional excavations were executed by Sir Charles Newton in 1857–1858 and the great treasures–including the colossal Lion of Knidos–were taken (by battleship) back to England. Missing, however, was the statue of Aphrodite.

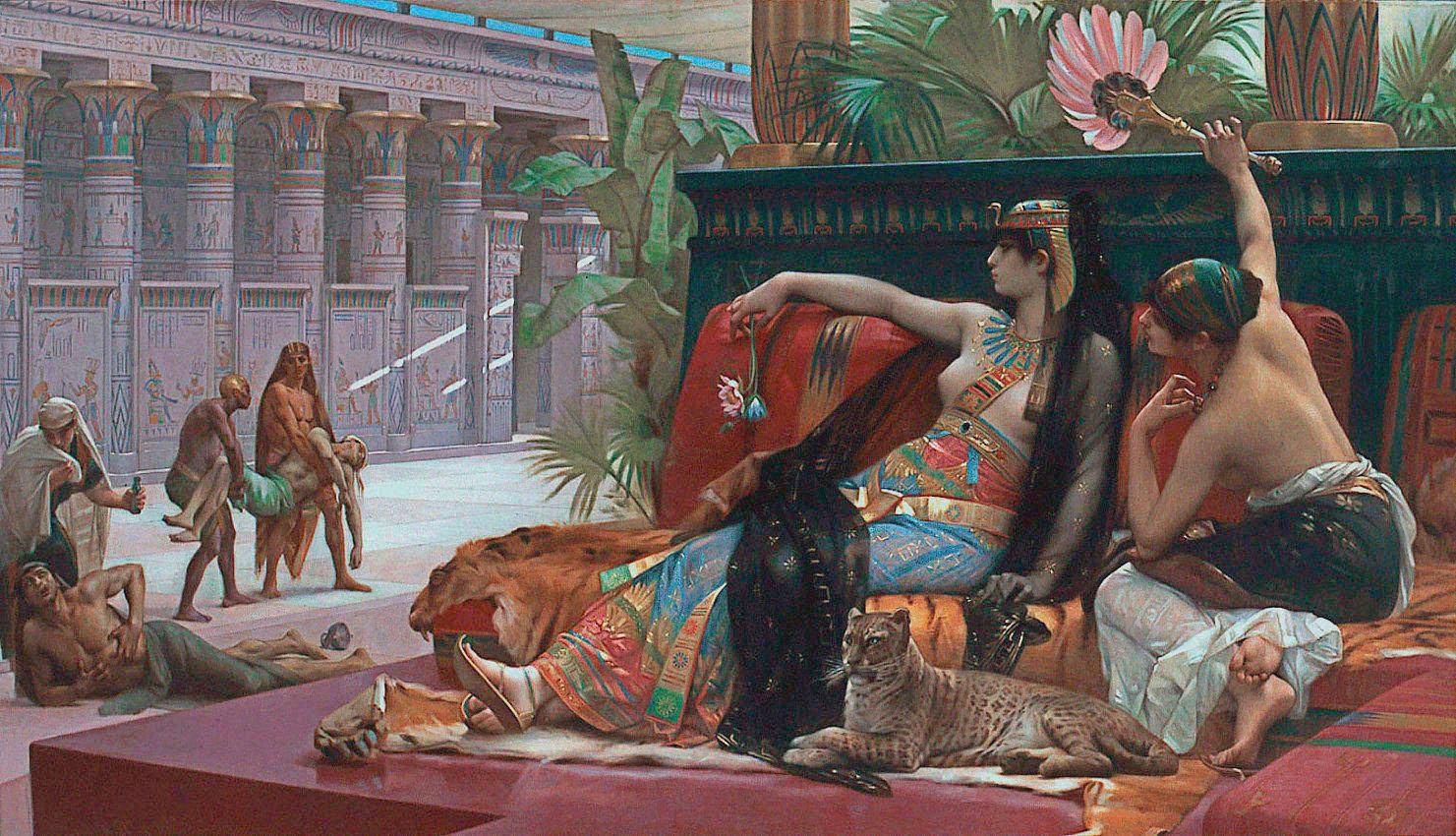

Aphrodite was an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, beauty, pleasure, and passion. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess Venus. In the Iliad she was the child of Zeus and Dione. She also had some well-known siblings including Apollo, Athena, Heracles, Helen of Troy, and the Cyclopes. Aphrodite was the surrogate mother and lover of the mortal shepherd Adonis, who was attacked by a wild boar and died in Aphrodite’s arms. With Athena and Hera, Aphrodite was one of the three goddesses whose feud resulted in the beginning of the Trojan War. But what history remembers most of Aphrodite, and what likely encouraged Praxiteles to bring her image to life, was her erotic beauty.

According to an account by Pliny the Elder, Praxiteles created two statues of Aphrodite (which were offered at the same price): one fully clothed and the other naked. The Greek town of Kos was horrified at the depiction of Aphrodite nude so they purchased the draped statue. Knidos bought the remaining Aphrodite and it was installed in a temple to the goddess where it gained a widespread cult-like following for its beauty. Coins issued in Knidos were minted in her honor. Later, King Nicomedes of Kos tried to buy naked Aphrodite from the Knidians promising to discharge their enormous state debt. The Knidians resolutely kept Praxiteles’ naked Aphrodite.

The statue became so widely known that epigrams were written of it. One anecdote has the goddess Aphrodite herself coming to Knidos to see the sculpture. Acknowledging her perfect likeness she says: “Paris, Adonis, and Anchises saw me naked. Those are all I know of. So how did Praxiteles contrive it?” A similar epigram is attributed to Plato: When Aphrodite saw her sculpture at Knidos she said, “Alas! Where did Praxiteles see me naked?”

The Knidos Aphrodite was different, in a decidedly erotic way. It is one of the first life-sized representations of the nude female form in Greek history, displaying an alternative idea to male heroic nudity. Praxiteles’ Aphrodite is shown reaching for a bath towel while covering her pubis, which, in turn leaves her breasts exposed. Up until this point, Greek sculpture had been dominated by male nude figures. Author Mary Beard writes in her book, How Do We Look: “The hands alone are a giveaway here. Are they modestly trying to cover her up? Are they pointing in the direction of what the viewer wants to see most? Or are they simply a tease? Whatever the answer, Praxiteles has established that edgy relationship between a statue of a woman and an assumed male viewer that has never been lost from the history of European art.”

Men were driven mad with desire for this image of Aphrodite. Pliny observed that some visitors to Knidos were “overcome with love for the statue.” The statue was so lifelike that it was said to “arouse viewers sexually as if she were a woman in flesh and blood.” In Erotes, an explicit essay written around AD 300 attributed to author Lucian of Samosata, a young man was once so overwhelmed by the image of Aphrodite that he broke into the temple at night and attempted to copulate with the statue. Upon being discovered by a custodian, he was so ashamed that he hurled himself over a cliff near the edge of the temple.

Sadly, Aphrodite of Knidos is no longer in existence. One theory is that the statue was removed to Constantinople (modern Istanbul), where it was housed in the Palace of Lausus in AD 475. When the palace burned the statue was lost. That was not the end, however, of the obsession with Aphrodite of Knidos.

Enter the curious appearance of American socialite archeologist Iris Cornelia Love.

Love claimed to be a direct descendant of both the explorer Captain James Cook and American founding father Alexander Hamilton, as well as the maternal great great granddaughter of Meyer Guggenheim. In 1969, with the Turkish archeologist Askidil Akarca, a granddaughter of the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Love sailed from Bodrum (ancient Halicarnassus) down the coast of Asia Minor to excavate the ruins of Knidos. On July 20, 1969, the day Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon, Love uncovered a circular marble platform at the Knidos site. Additional finds included the foundation of a circular building with eighteen columns, a life-sized human hand of Parian marble comparable in size to copies of the statue of Aphrodite of Knidos, numerous votive offerings dating from the archaic through Hellenistic periods, and an inscription in marble beginning: “Prax…” The team of young archeologists believed they had found the site of the temple that once housed perhaps the most famous statue of the ancient world and one of Pliny’s Seven Wonders–Praxiteles’ Aphrodite.

The excavated ruin many believe is the Temple of Aphrodite Euploia viewed from the cliff above at Knidos, Turkey. Flying Fish appears in the top right of the image. Photograph: © Jeffrey Cardenas

The discovery propelled Iris Cornelia Love to the kind of fame very few archaeologists achieve. She found herself on the front page of The New York Times, on prime-time national television interviewed by Barbara Walters, photographed by Harry Benson, partying with Andy Warhol. Tabloids ran headlines such as “Love Finds Temple of Love” and referred to her as “the mini-skirted archaeologist”. The discovery attracted intense international media attention when it was presented at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America. It also attracted many famous guests to the excavation site, including Mick and Bianca Jagger.

This fanfare called Love’s interpretation of the discovery into question. Critics accused her of converting the excavation into an exclusive holiday spot. Noted Turkish archaeologists disputed her conclusions. The Turkish government revoked her research license for Knidos. Love subsequently retired from archeology, devoted herself to breeding dachshunds (for which she won several prizes), and lived in Greece, Italy, and New York with her partner of many years, tabloid journalist Liz Smith. Iris Cornelia Love died this year at age 86, after being diagnosed with Covid-19.

I sit atop the jagged cliff overlooking the ruin of the Temple of Aphrodite Euploia and reflect upon myth and reality. (Could this be the same ledge where the besotted youth plunged to his death after being caught in flagrante delicto with the marble statue?) There is heat emanating from the rock and the quintessence of being in a rare place. I often wonder what it is that drives my ship. On this day it is the mythology of Aphrodite that puts fresh wind in my sails.

SOURCES

- Erotes: “A Dialogue Comparing Male and Female Love,” attributed to Lucian of Samosata, 2nd century AD

- The Venus Pudica: “Uncovering Art History’s Hidden Agenda’ and Pernicious Pedigrees,” Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts.

- Aphrodite of Knidos: Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology & the Ancient World,

Brown University - Pliny the Elder: Natural History XXXVI.4.20-I

- Iris Love, Archaeologist who Discovered the Temple of Aphrodite: The Telegraph Obituaries, May 5, 2020

- Love Among the Ruins: Departures, Martin Filler, March 30, 2010

- Epigrams Plato: Wikipedia.org

- Circe: Madeline Miller

- The Aphrodite of Knidos: YouTube, Faces of Ancient Europe October 18, 2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkwjgv3Nr90

Please subscribe at the bottom of this page so that you don’t miss a new update, and consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy following the voyage of Flying Fish. Your comments encourage me to continue writing.

If you would like to follow the daily progress of Flying Fish into the Mediterranean, and onward, you can click this link: https://forecast.predictwind.com/tracking/display/Flyingfish

To see where Flying Fish has sailed since leaving Key West in 2017, click here: https://cruisersat.net/track/Flying%20Fish

Instagram: FlyingFishSail

Facebook: Jeffrey Cardenas

Text and Photography © Jeffrey Cardenas 2020

I mention in an earlier post that 130,000 years of human civilization in the Eastern Mediterranean might be a factor in explaining why I have seen so few fish underwater during my first month of exploring this coastline in Flying Fish.

In fact, the species loss here has been exacerbated in only the past decade and a single predatory fish may bear some of the responsibility. The first lionfish in the Mediterranean was officially reported in 2012. Other divers have seen them even earlier. Still, these fish originating from the Indian Ocean are newcomers to the neighborhood. Now biologists fear the population of this predator with virtually no natural enemies may be out of control in the Mediterranean as it is elsewhere in the world.

Marine biologists with the Cypriot Enalia Physis Environmental Research Centre say lionfish first appeared in the waters off Cyprus in 2012. Since then the number of lionfish has exponentially increased not only in Cyprus but now also in Turkey and around some of the southern Greek islands. “Wherever you dive you can now see the lionfish in masses,” reported Louis Hadjioannou, research director at Enalia.

The Mediterranean invasion of lionfish resembles that of the western Atlantic Ocean. Lionfish were first recorded off the coast of Florida in 1994, but only 20 years later it was estimated that there were up to 1,000 lionfish per acre of coastline. A female lionfish can produce two million eggs a year. Marine biologists say they could be reducing Atlantic reef species diversity by up to 80%.

The lionfish’s “exponential rise” in the Eastern Mediterranean was facilitated by the widening of the Suez Canal—completed in 2014—and warming regional water temperatures, according to Jason Hall-Spencer, a marine biology professor at Britain’s University of Plymouth. The cooler waters of the western Mediterranean, he reported, have largely been spared of lionfish for the moment.

Culling lionfish for food has helped reduce their numbers in other parts of the world. I have yet to see a lionfish in a Turkish fish market but stranger things make their way to the dinner table here–Koc Yumurtasi (ram’s testicles), for example. I look forward one day soon to preparing whole fried lionfish to my new Turkish friends.

I mention in an earlier post that 130,000 years of human civilization in the Eastern Mediterranean might be a factor in explaining why I have seen so few fish underwater during my first month of exploring this coastline in Flying Fish.

In fact, the species loss here has been exacerbated in only the past decade and a single predatory fish may bear some of the responsibility. The first lionfish in the Mediterranean was officially reported in 2012. Other divers have seen them even earlier. Still, these fish originating from the Indian Ocean are newcomers to the neighborhood. Now biologists fear the population of this predator with virtually no natural enemies may be out of control in the Mediterranean as it is elsewhere in the world.

Marine biologists with the Cypriot Enalia Physis Environmental Research Centre say lionfish first appeared in the waters off Cyprus in 2012. Since then the number of lionfish has exponentially increased not only in Cyprus but now also in Turkey and around some of the southern Greek islands. “Wherever you dive you can now see the lionfish in masses,” reported Louis Hadjioannou, research director at Enalia.

The Mediterranean invasion of lionfish resembles that of the western Atlantic Ocean. Lionfish were first recorded off the coast of Florida in 1994, but only 20 years later it was estimated that there were up to 1,000 lionfish per acre of coastline. A female lionfish can produce two million eggs a year. Marine biologists say they could be reducing Atlantic reef species diversity by up to 80%.

The lionfish’s “exponential rise” in the Eastern Mediterranean was facilitated by the widening of the Suez Canal—completed in 2014—and warming regional water temperatures, according to Jason Hall-Spencer, a marine biology professor at Britain’s University of Plymouth. The cooler waters of the western Mediterranean, he reported, have largely been spared of lionfish for the moment.

Culling lionfish for food has helped reduce their numbers in other parts of the world. I have yet to see a lionfish in a Turkish fish market but stranger things make their way to the dinner table here–Koc Yumurtasi (ram’s testicles), for example. I look forward one day soon to preparing whole fried lionfish to my new Turkish friends.