© Jeffrey Cardenas 2024

A thin red line bisects the island of Hispaniola. On one side of the line, there is a world of chaos and rage this week as 4,000 of Haiti’s most notorious inmates escaped prison in a machete-wielding bloody rampage. They are terrorizing the countryside and remain loose in the shadows of the island as Haiti declares a state of emergency.

On the same island, but on the other side of this geopolitical line, is the Dominican Republic. This is a pastoral environment of natural beauty where nature thrives and men and women work peacefully with their hands to feed their families.

Several weeks ago, Stella Maris ghosted up to an isolated shoreline of Hispaniola–on the Dominican side. Los Haitises National Park is the Dominican Republic’s most important natural and cultural preserve. Amid the quiet pockets of dense mangrove and subtropical forest, spectacular limestone walls rise from the sea. It is difficult to comprehend why one-half of this island is literally and figuratively on fire, while on this half of Hispaniola, there is an undisturbed natural world of calm and tranquility.

One of the reasons I sail to isolated parts of the world is to try to understand this disparity. Sailing is not always just a simple escape from reality; I recognize the hardship, hate, and despair that is consuming so much of the world around us. Sailing helps me find a balance. As I travel, I choose to be a collector of moments that bring joy and hope. I found those moments in the nature of Los Haitises.

Along this wild shoreline, it is also possible to feel the ancient life force of the Taíno inhabitants who settled the entire island of Hispaniola 2,000 years ago. Christopher Columbus colonized the island of Hispaniola during his first voyage to the Americas in 1492. That voyage was the beginning of the end for the indigenous people. The native Taínos quickly suffered a steep population decline due to brutal enslavement, warfare, and intermixing with the Spanish colonizers.

Two hundred and fifty years later, a political division of Hispaniola occurred as France and Spain each struggled to control the island. They resolved their dispute in 1697 by splitting the island into two colonies, France holding what would be Haiti to the west and Spain taking control of the Dominican Republic to the east. Those colonial chains were finally severed on both sides of the island after two bloody wars of independence in 1804 and 1865. Haiti would eventually become the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, while the Dominican Republic developed into one of the largest economies in the region.

The Taíno indigenous people, meanwhile, were the ultimate losers in this struggle. Some 90% of Taíno civilization was lost to a European genocide of slavery and sickness. Remnants of the lost Taíno culture can still be found in the 618-square-mile Los Haitises National Park.

Click on a picture in this gallery for a high-resolution version of the image

We anchor the Stella Maris to explore the massive caves emerging from the limestone karsts on the rugged southern shore of the Dominican Republic’s Golfo del Samaná. Deep inside the more remote caves there are authenticated petroglyphs and pictographs dating back a thousand years. The images depict birds, whales, and, on one wall, the fading image of an ancient shaman. Sadly, where tour groups have frequented the caves, there is also graffiti and empty soda bottles.

Ginny and I hike an overgrown trail up a steep conical hillside to the ruins of a cacao, ginger, and breadfruit plantation. Nothing remains of the overgrown settlement except a lone, untethered donkey standing in a rare patch of sunlight nibbling at the subtropical understory. A critically endangered Ridgway’s Hawk watches our movement from a high branch. A tiny Vervain Hummingbird hovers near a patch of ginger. Later, I find a rock-polished donkey shoe buried in the mud of the trail.

Author Jared Diamond, Professor of Geography and Physiology at the University of California, writes that there is no simple answer to the conundrum of Hispaniola. In an interview with NPR, he said, “It’s a complex mix of history and environment, plus social and political policy.”

Flying from Miami to Santo Domingo, the border is well defined: On the Haitian side, the earth is a scorched brown with two centuries of deforestation and erosion. The Dominican side, where conservation initiatives are apparent, is a verdant green. Six months ago, the Dominican Republic and Haiti closed the land, sea, and air borders between the two countries.

Today, gangs in Haiti surround the country’s main airport in the capital of Port-au-Prince, making it impossible for Prime Minister Ariel Henry to return to Haiti after an international trip abroad. Haiti’s most prominent gang leader, Jimmy “Barbeque” Chérizier, issued an ultimatum, warning that “if Ariel Henry does not resign … we’ll be heading straight for a civil war that will lead to genocide.”

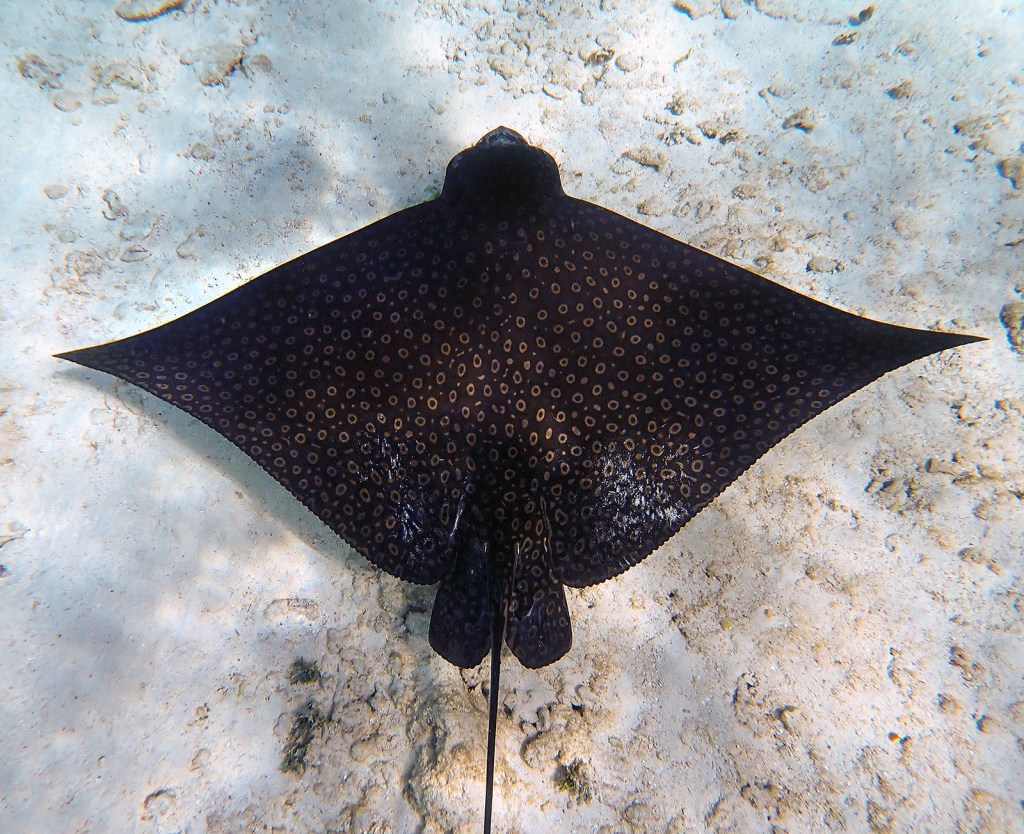

And the moments of joy and hope? Magnificent frigatebirds spiral above the islands of Los Haitises, the chittering of black-crowned tanagers can be heard deep within the forest, and on the water, humpback whales migrating from the Arctic arrive in the spring to give birth and nurture their young in the whale sanctuary of Golfo del Samaná.

In turbulent times like these, Los Haitises can also be a sanctuary for human beings.

As always, sailing is not just about the wind and the sea; the places, the flora, fauna, and people encountered along the way are equally important.

Please click “Follow” so that you don’t miss a new update,- and please consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy following the voyage. I welcome your comments and will always respond when I have an Internet connection. I will never share your personal information.

Instagram: StellaMarisSailing / Facebook: Jeffrey Cardenas

Text, Photography, and Videos © Jeffrey Cardenas 2024

Let this be a time of grace and peace in our lives – Rev. John C. Baker