As I sail north out of the Caribbean Sea, I have spent much of the last month diving over dead and dying coral reefs. I try not to focus on this. There is enough despair in the world these days without highlighting any more of it. I prefer instead to acknowledge isolated moments of beauty and hope. This morning, while snorkeling over another reef of broken coral rubble, I was heartened by the sight of a tiny coral farm attached to the bottom of the bay.

Bahía Tamarindo Grande is on the northwest coast of the island of Culebra in the Spanish Virgin Islands. It is an isolated stretch of land with no development and no roads. There are flowering frangipani, a symphony of birdsong echoing in the trees, and a deserted white sandy beach. In contrast, a sign warns visitors not to pick up unexploded ordnance. This area east of Puerto Rico was once a bombing and artillery range for the U.S. military. Nearby, a Sherman tank is rusting on the beach.

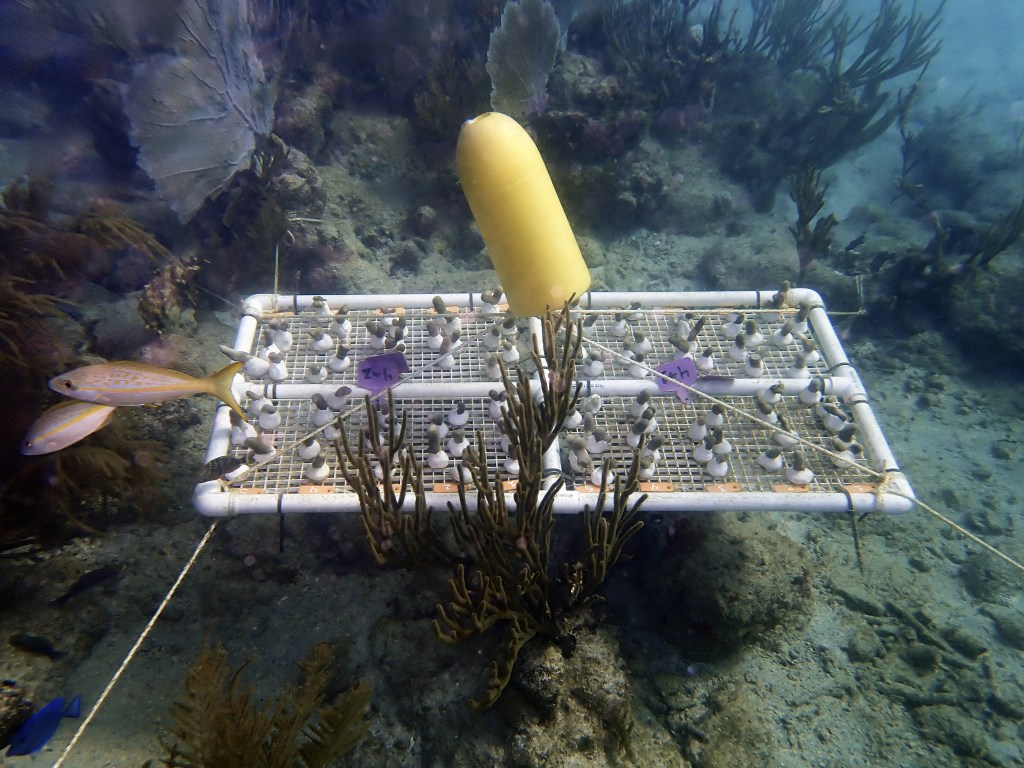

The coral farm, suspended 20 feet underwater, has no identification plate or surface buoy to mark its location. It’s not shown on any nautical charts. It is simply a submerged platform the size of a backyard vegetable plot. Instead of growing lettuce and carrots, some anonymous person has planted branched finger coral. About 80 coral nubs are mounted on a plastic grid, and they are thriving.

There is nothing new about the aquaculture of coral. One of the first successful coral propagation attempts occurred at New Caledonia’s Nouméa Aquarium in 1956. Commercial coral propagation began in the United States in the 1960s. Still, it wasn’t until worldwide coral populations began to crash in the 1980s that the industry focused on propagating coral for oceans instead of aquariums.

Then, in April 2006, the Margara, a 750-foot tanker carrying over 300,000 barrels of fuel oil, ran aground on a shallow coral reef in Puerto Rico’s Bahía de Tallaboa. No oil was spilled, but the grounding and efforts to remove the vessel destroyed 6,755 square meters of reef, including six species of coral protected under the Endangered Species Act. Emergency restoration by NOAA and the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources saved approximately 10,500 coral colonies in the affected reef by using farmed corals from nurseries and transplanting them back onto the ocean floor.

As coral populations diminish due to human negligence and climate change, it may seem that coral is disappearing faster than it can be replaced. This does not deter the efforts of research and conservation groups such as the Mote Marine Laboratory, which has restored more than 216,000 corals to Florida’s reefs. Notably, some restored corals are now naturally reproducing to create new generations of coral.

The Coral Restoration Foundation in the Florida Keys is also succeeding in growing coral that reproduces both sexually through spawning and asexually through fragmentation (where a small piece of coral can reattach and develop into a new colony). Since 2012, the Coral Restoration Foundation has transplanted more than 220,000 corals onto Florida’s reef, restoring over 34,000 square meters of habitat.

Back in Culebra, local commercial fishermen proposed the establishment of the Luis Peña Channel Natural Reserve to replenish local fish stocks and protect the coral reefs. This reserve encompasses Bahía Tamarindo Grande, home to the coral farming garden plot. It is the first no-take marine protected area designated in Puerto Rico. The mission statement is simple: The health of coral reefs directly depends on strong reef fish populations. Fish and other animals, such as lobsters and shellfish, rely on the health of the coral reef. The livelihoods and culture of the people of Culebra depend on healthy coral reefs.

As always, sailing is not just about the wind and the sea; the places, the flora, fauna, and people encountered along the way are equally important.

Please click “Follow” so you don’t miss a new update, and please consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy connecting with the voyage. I welcome your comments and will always respond when I have an Internet connection. I will never share your personal information.

An additional website, www.JeffreyCardenas.com, features hundreds of fine art images—underwater, maritime landscapes, boats, and mid-ocean sailing photography–from exotic locations worldwide.

Upcoming Exhibition: “On the Reef” will be exhibited in The Studios of Key West’s Zabar Project Gallery, on view from January 2–30, 2025.

Instagram: StellaMarisSailing / Facebook: Jeffrey Cardenas

Text, Photography, and Videos © Jeffrey Cardenas 2024

Let this be a time of grace and peace in our lives – Rev. John C. Baker