There is a story from every leg of the journey as Flying Fish has traveled around the world. The story for this passage across the Atlantic is one of brotherhood.

My brother Bob and I are salt and pepper, and I don’t just mean our hair color. Bob is an analytical thinker; I look at clouds and think they resemble dogs. Bob sees something broken, and he repairs it; I see something broken, and although I try to repair it, I inevitably make the problem worse. Bob is gregarious; I am a social misfit. Bob sells dream houses; I sell dreams.

We have just completed a 2,500-mile passage from Cape Verde to Antigua aboard Flying Fish. This is not our first transatlantic passage together. In 1976, we sailed with our sisters and parents from Florida to Portugal in a Cal 43 named Free Spirit. Two years later, our parents allowed Bob and me to sail Free Spirit from Gibraltar back to Florida. That’s when things went sideways. That voyage led to a weird estrangement with my brother, lasting over 45 years.

Those many years ago, I had been caretaking Free Spirit in the Mediterranean. Bob was writing his thesis on the sexual behavior of clams at Florida State University. When our parents asked us to bring the boat home, they gave Bob $500 for provisions. Bob arrived in Gibraltar with two buddies, an Israeli hitchhiker named Dadi, and a Moroccan rug. Bob had made a side trip to Tangier and used the $500 to buy the rug. There was no money remaining for provisions.

“How are we going to eat, Bob?” I asked.

“Haven’t you ever scavenged behind restaurants and grocery stores?” he answered. “They throw away a bunch of really good food.”

And so Free Spirit was provisioned for a long ocean passage with sacks of rotting produce obtained by dumpster-diving behind Gibraltar’s restaurants and grocery stores.

Bob is three years older than me. Before he arrived in Gibraltar, I sailed Free Spirit for months through the Mediterranean. Once we met up, Bob and I each assumed that we personally had the responsibility as captain to bring the ship safely home. Our parents never made the designation. They probably thought that their two boys were mature enough to work it out for themselves. Apparently, we were not.

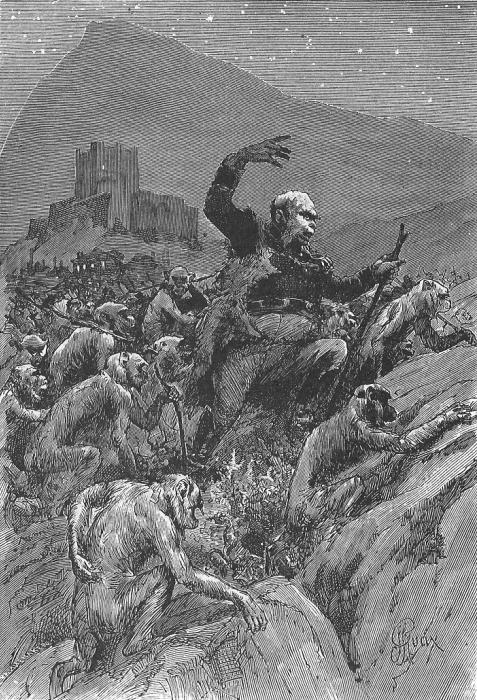

We fought about everything from sail changes to course plotting to who slept where. It got worse as we got hungrier. Not even the fish cooperated by taking our trolled lures. We began rationing food (Here’s a quarter of a rotten potato for your supper.) To make matters worse, we had sailed into a high-pressure ridge west of the Canary Islands and were becalmed for days. Free Spirit’s engine didn’t work. The battery had no power to start the engine, and there was no way to charge the battery. It was an ill-fated voyage. I kept thinking, “This is going to end up being a sea-going Lord of the Flies.”

Halfway across the ocean, the fishing line we trailed behind Free Spirit finally came tight. A marlin had become entangled with a white rag lure we had been trolling behind the boat. Bob and I battled to reach the rod first. He strong-armed the marlin to the side of the sailboat. Then, with savage appetite, the crew of Free Spirit descended upon the marlin with knives, cutting fillets and eating some of the fish raw.

After 30 days at sea, we made landfall in Tobago. I left Free Spirit soon after that. Bob and his two buddies continued onward. (The Israeli hitchhiker vanished, much to the wrath of local immigration authorities.) My brother and I never fully recovered from the acrimony of that trip. Our lives went in different directions. We were always polite when we saw one another, but for nearly a half-century, there was a distance between us that we had not found a way to bridge.

Late last year, as my wife Ginny and I were en route from the Canary Islands to the Caribbean aboard Flying Fish, we encountered a serious issue that jeopardized not only the completion of that passage but our safety as well. We had communication via satellite phone. I called on my family for help–including my brother, who was quick to respond. Bob stepped up and, at all hours of the day and night, he helped work the problem. Ginny and I diverted to Cape Verde to complete repairs. Bob’s efforts over those difficult four days were the catalyst that reactivated our brotherhood. Sadly, Ginny’s trip was over, but Bob agreed to join me aboard Flying Fish for another shot at the transatlantic.

This 2,500-mile passage across the ocean with Bob was fast–15 days in sloppy weather with spitting rain, wind speeds to 35 knots, and steep swells from different directions that rolled the boat from gunwale to gunwale. We split our time into four-hour watches, but when one of us needed more rest, the other was happy to pick up the slack. Bob did more than his share of feeding us. This time the fish did cooperate, and Bob exhibited his culinary skills, including a creative dish of fried sargassum weed (no rotten potatoes.)

Our night watch conversations aboard Flying Fish danced around the fateful voyage of Free Spirit 45 years ago. But, because of our selective memories, or for the simple desire not to dredge up ill will, we chose instead to focus on the present. On this passage to the Caribbean, I think my brother and I both understood that we were experiencing something that far transcended just another sailboat ride. We were strengthening our brotherhood and rebuilding the bridge.

For the daily details and observations of our passage from Cape Verde to Antigua, check out the notes on this page. Click on the box labeled “Legends and Blogs” for the daily passage notes.

Thanks for sailing along with us as Flying Fish resumes its passage into the Caribbean and toward Key West.

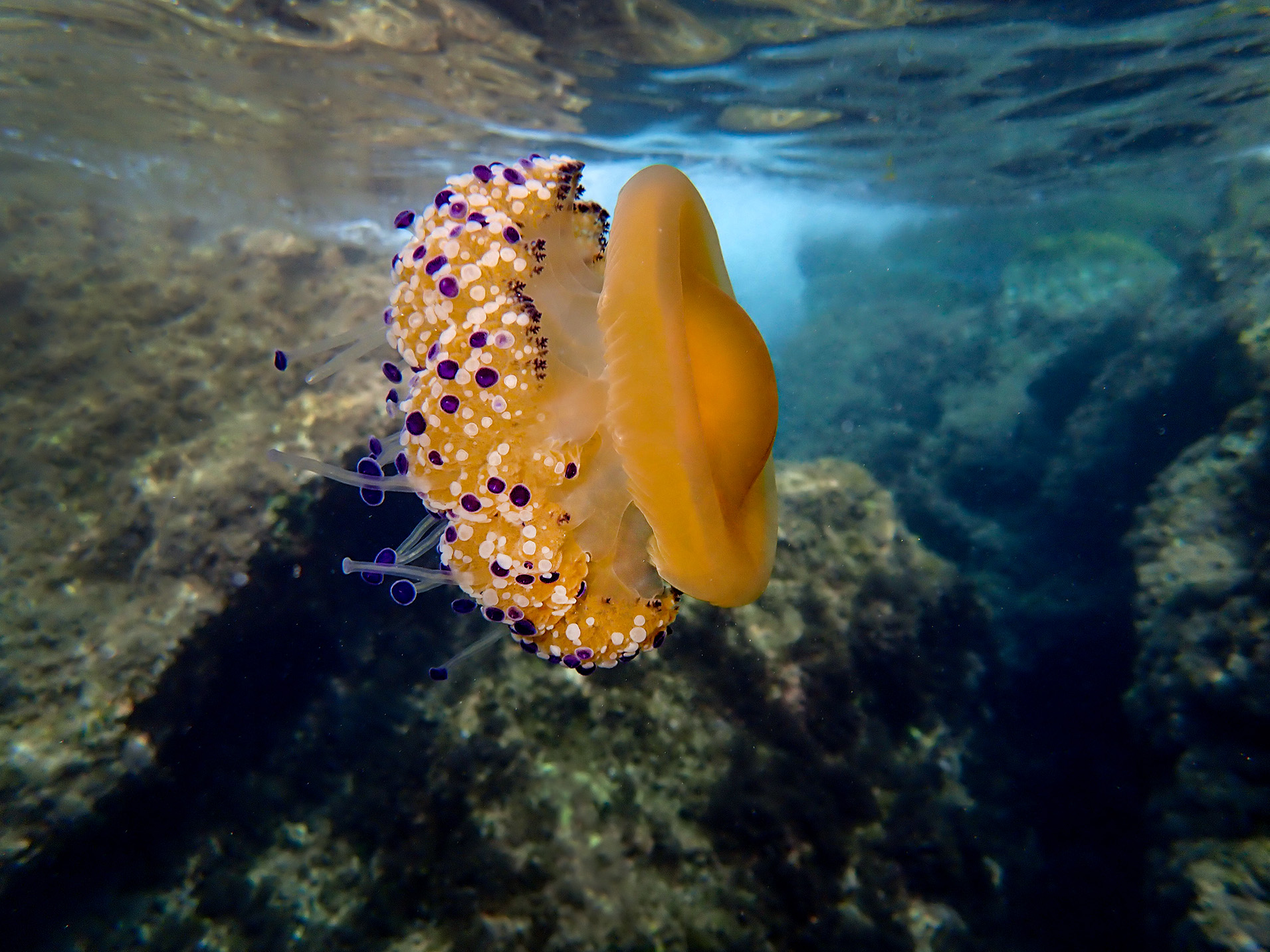

As always, Sailing is not just about the wind and the sea; equally important are the places, the flora, fauna, and people encountered along the way.

Please click “Follow” at the bottom of this page so that you don’t miss a new update,- and please consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy following the voyage of Flying Fish. I welcome your comments, and I will always respond when I have an Internet connection. I will never share your personal information.

You can follow the daily progress of Flying Fish, boat speed (or lack thereof), and current weather as we sail into the Atlantic by clicking this satellite uplink: https://forecast.predictwind.com/tracking/display/Flyingfish.

To see where Flying Fish has sailed since leaving Key West in 2017, click here: https://cruisersat.net/track/Flying%20Fish.

Instagram: FlyingFishSail

Facebook: Jeffrey Cardenas

Text and Photography © Jeffrey Cardenas 2021

Let this be a time of grace and peace in our lives – Fr. John Baker