A mid-winter squall thrashes the coconut atoll of Maupihaa, a last outpost of French Polynesia. Photography: © Jeffrey Cardenas

Winter has arrived in mid-June as Flying Fish negotiates the changes in longitude on its journey westward around the globe. Here the solstice on June 21 is the shortest day of the year. After a lifetime in the northern hemisphere I feel like I am upside-down.

For many sailors the departure from French Polynesia to points west—the Cook Islands, Tonga, Samoa, and Fiji—marks the end of the Coconut Milk Run, the forgiving passage of trade wind sailing from the Americas to Tahiti. The party is over in Bora Bora.

The South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCV) dominates the weather now in the Central South Pacific. Even though the cyclone season is months away the fierce winter storms passing well south bring an unsettled climate here. At this longitude Flying Fish has sailed into an area of the Pacific Ocean known as The Dangerous Middle.

West of Tahiti, weather windows must now be more carefully consulted. Mid-winter fronts arrive every seven to 10 days. When they descend upon these waters the ocean is anything but pacific. I am sailing solo again. This brings everything into sharper focus. There is no margin for error.

I waited nearly two weeks in Bora Bora for the inclement weather to pass (not exactly hardship duty Bora Bora) and finally seeing an opening on the weather charts I departed for the island of Maupiti, a short 25 miles west. Maupiti is a French Polynesian island of soaring cliffs, luxuriant vegetation, and magnificent beaches. There are braserries and warm baguettes. But within hours of my departure from Bora Bora the wind returned to near 30 knots and seas increased to 12 feet. Squalls reduced visibility. Maritime navigational notes warn against attempting an entry into the exposed south pass of the Maupiti atoll when seas exceed two meters. The warning is well founded. As I approached the pass I could see set waves breaking completely across the only entrance to the lagoon. A current of five knots was flowing out of the narrow cut between two spurs of the coral reef.

Maupiti may be one of the most scenic landfalls in the South Pacific, an island not to be missed. Maybe, but for me it will have to be in another lifetime. I took one last look; I could almost smell the French pastries. However, running this pass in Flying Fish under these conditions would be certain disaster. There was also no turning back against the wind and seas to Bora Bora. I continued on, a night passage of more than 100 miles, to the atoll of Maupihaa.

Maupihaa is a low coconut atoll with virtually no radar return. Arriving in a torrential rainstorm I was first able to make visual contact only because of the massive swells breaking again the reef. This is also a “single pass atoll”, meaning all of the water that flows over the reef and into the lagoon has only one pass from which to exit. In stormy weather this creates a raging outgoing current. Although the pass is located on the protected northwest corner of the atoll the navigation notes state, “Passe Taihaaru Vahine is one of the trickiest passes in French Polynesia. Currents can reach six knots with whirlpools and rips that can make this entrance impassable.” An Australian sailor in a boat already anchored in the lagoon (he had been waiting there for nearly 10 days for better weather) talked me through the pass over the VHF radio like an air traffic controller guiding a plane in on an instrument approach. “Look for a break in the coral shelf,” he said, “and then come in hot because any hesitation will sweep you sideways onto the rocks and there is not enough width in the pass to turn around.”

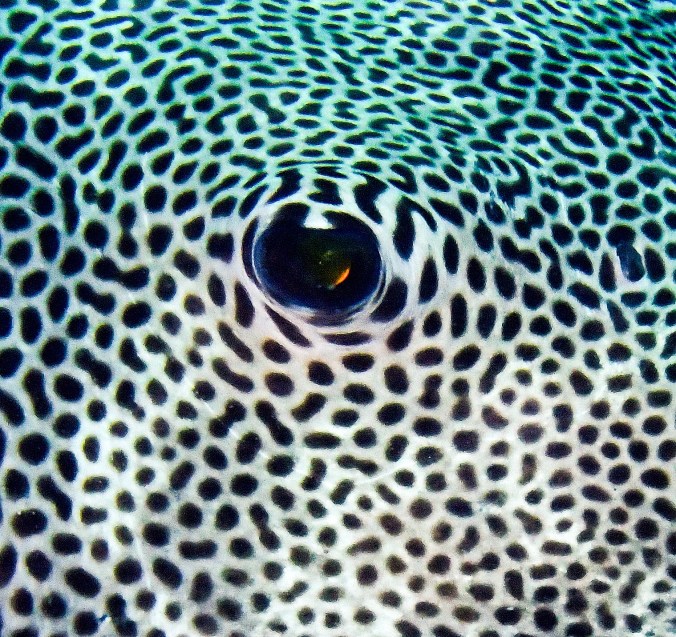

Hours later after my heart rate returned to normal, I learned that Maupihaa was unlike any other island I had sailed into in French Polynesia. In 1998, Cyclone Martin swept over the island destroying 75% of the trees and vegetation, and all but one of the houses. Now less than 10 families live here in open-air huts sustained by a hard-scrabble life of harvesting copra (coconut meat for oil). A supply barge arrives only a couple times each year. There are no hotels, no roads, no shops. Barter among the inhabitants is the only currency. Thousands of seabirds inhabit the atoll and the lagoon abounds with sharks, turtles, and colorful tropical fish. Aside from the constant roar of seas breaking on the atoll reef, there are no other sounds–except for the incessant barking of dogs.

“The locals have invited you to dinner ashore,” the other sailor said once I had secured my anchor. “Expect to be served tern eggs, coconut crabs, and dog stew. Bring liquor.”

Dog stew?

We are not in Kansas anymore, Dorothy. And in the Dangerous Middle, Toto is on the menu.

Track the passage of Flying Fish here: https://forecast.predictwind.com/tracking/display/Flyingfish