Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan this week announced the end of COVID lockdown restrictions for most parts of Turkey including Didim, where Flying Fish is undergoing final preparations for departure westward and the continuation of her circumnavigation. Didim is also the location of an archeological site, the Temple of Apollo at Didyma, where pilgrims consulted an oracle and received a divine prophecy of future events. Some divination would be helpful in these uncertain days. Released from lockdown, I spend the day wandering among the marbled Doric columns of the Didyma ruin and reflect on the bizarre history of this place. Maybe the oracle will tell me how the proverbial winds will blow for Flying Fish in the coming year.

Didyma was once the most renowned sanctuary of the Hellenic world. Some of the earliest archaeological pieces discovered here date back to the 8th century BC. In its heyday, the colossal Temple of Apollo was larger than even the Parthenon in Athens. Its size and influence grew around a small natural spring which was believed to be the source of the oracle’s prophetic power.

Apollo was one of the Olympian deities in Greek and Roman mythology. He was the son of Zeus, the king of the gods. In the Iliad, Apollo is a healer. He cured people during pandemics, yet he was also a god who could bring about disease and death with a shot from his arrow. Apollo was a god who could spread disease, but he could also prevent it. He was a god of limitless power.

Apollo was said to have been born under a palm tree on a floating island named Delos in the Aegean Sea. When his mother Leto gave birth “everything on Delos turned to gold and the island was filled with ambrosial fragrance. Swans circled the island seven times and the nymphs sang in delight.” Apollo’s birth fixed the floating island of Delos to the bottom of the ocean. It lies 100 miles due west of Didyma and Flying Fish.

I became fascinated with Apollo because of his distinction as a patron and protector of sailors, a duty he shared with Poseidon. In mythology, Apollo is seen helping heroes who pray to him for a safe journey. Once, when he spotted a ship of Cretan sailors caught in a storm, he assumed the shape of a dolphin and guided their ship safely to Delphi. When the Argonauts were foundering at sea, Jason prayed to Apollo for help and the god used his bow and golden arrow to shed light upon an island where the Argonauts found shelter. Apollo helped the Greek hero Diomedes escape from a great tempest during his journey homeward, and he sent gentle breezes that helped Odysseus return safely from the Trojan War.

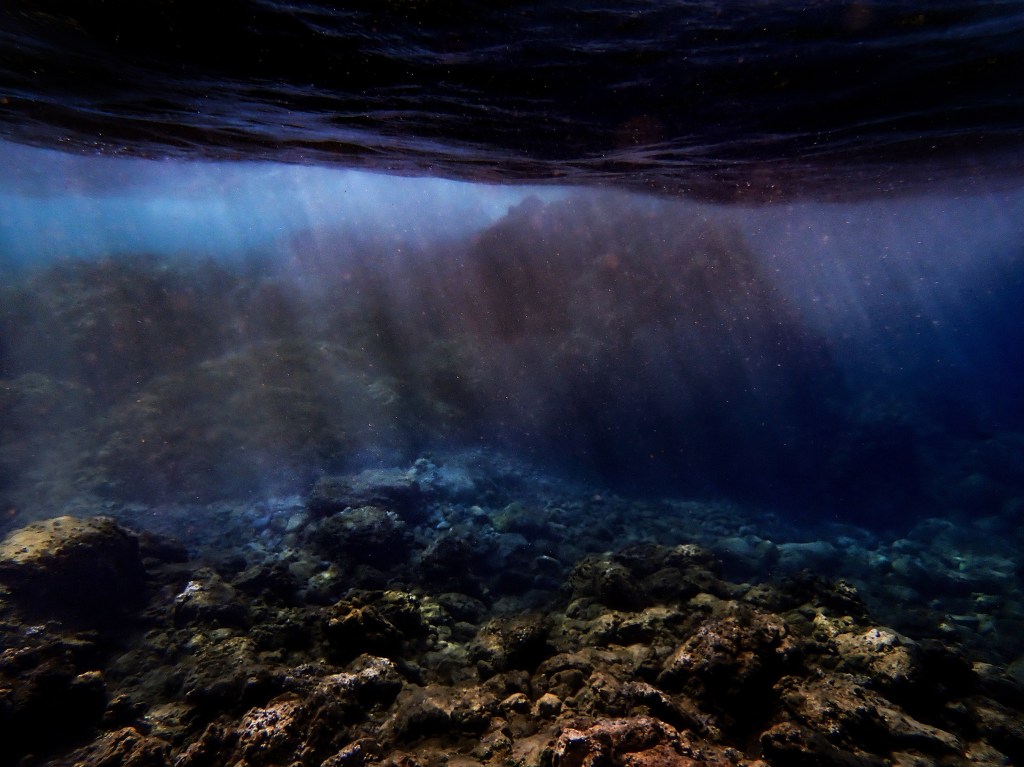

If a god had such powers over mortals then surely, it was thought, he could also foretell the future. Temples to Apollo were built throughout the Aegean but among the most extravagant was the grand temple to Apollo built over a sacred spring in the Anatolian region of what is now Turkey. Rows of Ionic columns were ornamented with reliefs of griffins and gorgons. A frieze above the columns featured monumental heads of Medusa. At the entrance to the temple there was an altar for Apollo, which, according to Greek historians of the second century AD, was made of the blood and ashes of sacrificed animals. A festival was held each year in Didyma called the Didymeia. Pilgrims walked 20 kilometers along the Sacred Way from Miletus to Didyma to participate in the celebration of Spring. Poets, musicians, and artisans strolled among the courtyards. A theater and stadium at the temple hosted events. Believers consulted the oracle. In the oracular procedure, reconstructed by historians and archeologists, a priestess inspired by Apollo sat on a foundation above the oracle spring. It is likely that the priestess delivered Apollo’s predictions in classical hexameters, as at Delphi. Nothing was written, however, and there was no record of whether the oracle predicted what would happen next.

The Temple of Apollo at Didyma was plundered and destroyed in 494 BC by the Persian king Darius, known for his skill of deception and of lancing his enemies. (In an interesting footnote, Darius was said to have been crowned after winning a wager with three other candidates for the monarchy. They agreed to meet before daybreak, each on his horse, and the first horse to neigh at the sunrise would be named the new king. Darius cheated. His servant made the horse neigh by letting the animal smell scent rubbed from the genitals of a mare. The horse’s neigh, accompanied by lightning and thunder from a storm, convinced the other candidates to accept Darius as the new king.) During the raid of Didyma, the Persians carried away a bronze cult statue of Apollo and it was reported that the sacred spring ceased to flow. The oracle was silenced. Didyma remained a ruin until 331 BC when Alexander the Great, who by the age of 30 had created one of the largest empires of the ancient world stretching from Greece to northwestern India, conquered the Persians and re-consecrated the Didyma site. Callisthenes, the great-nephew of Aristotle and historian of Alexander, reported that the spring had once again begun to flow. The temple itself, however, seemed forever doomed.

Caligula had the heads removed from various statues of gods located across Rome and replaced them with his own.

Cassius Dio, Roman History Book LIX

Didyma was looted again in 277 BC, this time by the Galatians as they raided Greek cities in Asia Minor. Then pirates plundered Didyma in 67 BC. Julius Caesar declared Didyma a refuge for people facing persecution but still, the Temple of Apollo lay in ruin. Another Roman emperor, this time the notorious Caligula, also tried to resurrect the Didyma Temple of Apollo. Historians focus on Caligula’s cruelty, sadism, extravagance, and sexual perversion, presenting him as an insane tyrant. Once, during some games at which he was presiding, Caligula was said to have ordered his guards to throw an entire section of the audience into the arena during the intermission to be eaten by the wild beasts because he was bored. Caligula had the heads removed from various statues of gods located across Rome and replaced them with his own. He began referring to himself as a god when meeting with politicians, even dressing occasionally as Apollo. Meanwhile, Didyma languished.

The Roman emperors were not yet done with Didyma. In 303 AD, the emperor Diocletian sent a delegation to Didyma to ask the oracle what he should do about the growing number of Christians within the empire. The Christians were accused of upsetting the gods and preventing accurate prophecies. The oracle’s supposed response inspired Diocletian to launch the most severe and systematic religious persecution of Christians in Roman history. They, too, were thrown into the arenas with wild beasts. This marked the end of the oracle. And in 1493, an earthquake destroyed the Temple of Apollo at Didyma. It was never rebuilt.

Modern Didim is now a place fueled by a tourist industry that has gone into stasis during the COVID pandemic. Vacation villas pave the hillsides. Massive hotels remain virtually empty. The ruin of the Temple of Apollo at Didyma is incongruously located in a high-density neighborhood of modern apartment complexes. It is difficult to reconcile the immense history of Didyma–funded by the riches of Croesus, destroyed by Darius, resurrected by Alexander the Great, defiled by Caligula–with the current reality of people going about their business in Didim. There are banks and real estate offices, a home goods store, gas stations, mobile phone stores, and recently re-opened cafes and restaurants. And then, as you pass the Mine Market Liquor Store located near what was once the Sacred Way, there is the monumental Temple of Apollo. The ruin has been sparsely visited since COVID. It is as if daily life during the pandemic has made it too difficult to revisit the past. I walk alone among a great field of fallen columns. In the southeast corner of the ruin, next to the screaming face of a carved gorgon, I see a sliver of green among some moist ground. It is the sacred spring emerging from the earth.

SOURCES

- “Didyma” Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service

- “Didyma” The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion, Simon Price and Emily Kearns

- “The History of Apollo’s Temple at Didyma, As Told By Marble Analyses And Historic Sources“, Barbara Borg and Gregor Borg, Martin Luther University Halle Wittenberg

- “Darius I” World History Encyclopedia, Radu Cristian.

- “Hymn to Delos” Callimachus, Greek poet and scholar at the Library of Alexandria 310–240 BC

- “The Iliad” Homer

Please subscribe at the bottom of this page so that you don’t miss a new update, and consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy following the voyage of Flying Fish. I welcome your comments.

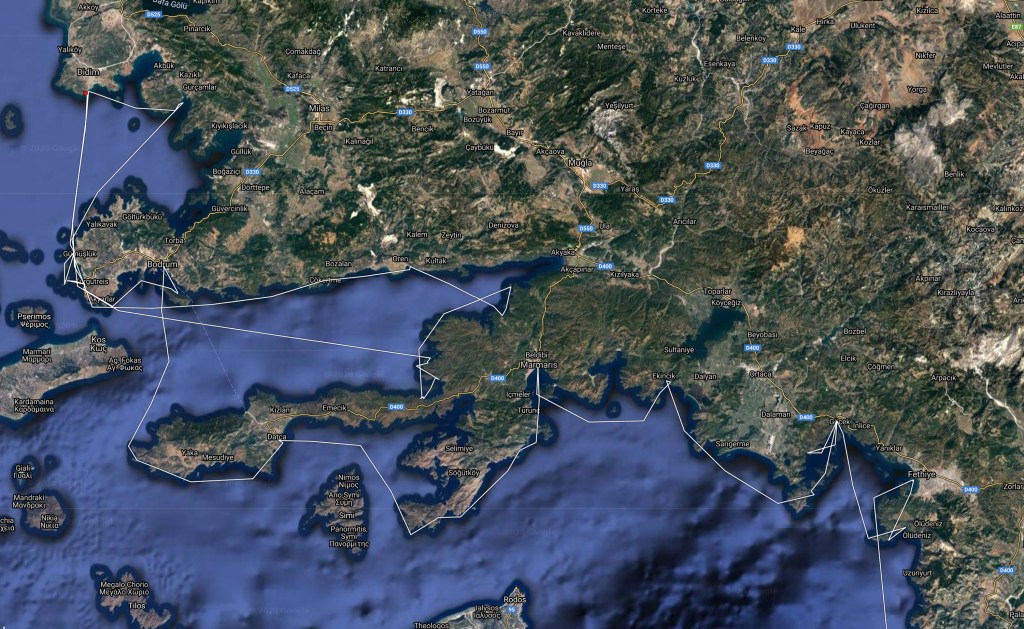

I hope to be underway aboard Flying Fish in late March 2021. Once the voyage restarts you can follow the daily progress of Flying Fish into the Mediterranean, and onward, by clicking this link: https://forecast.predictwind.com/tracking/display/Flyingfish

To see where Flying Fish has sailed since leaving Key West in 2017, click here: https://cruisersat.net/track/Flying%20Fish

Instagram: FlyingFishSail

Facebook: Jeffrey Cardenas

Text and Photography © Jeffrey Cardenas 2021

Let this be a time of grace and peace in our lives –Fr. John Baker