A passage has a life of its own. Like a good book, there is a beginning, various plotlines, drama, and then it ends. The 680-mile passage of Flying Fish last week across the eastern Mediterranean from Turkey to Malta was no exception.

- I felt some anxiety about my routing to Malta through Greek territorial waters. Greece and Turkey prohibit transit between their countries, and their war of words has recently escalated to saber-rattling.

- Weather became an issue. A ferocious meltemi wind developed, unforcasted, soon after I departed from Turkey.

- I experienced a startling “bump in the night” as Flying Fish’s keel met unseen rocks in a dark anchorage.

- The meltemi turned into winter with freezing rain coating the deck.

- As I continued into the Mediterranean, hundreds of merchant ships were stalled en route to Suez because a massive container ship had gone aground, closing the entire canal.

- And in the middle of it all, I once again lost critical onboard electronics. Both the AIS and the autopilot became inoperative. I was electronically invisible to shipping traffic and, with my autopilot gone, I couldn’t even take my hands off the wheel to pee overboard.

Nobody said this was going to be easy.

The route from Turkey to Malta was an initial point of concern. Travel between ports in Turkey and Greece–COVID notwithstanding–has been shut down for months because of territorial sea disputes. Tensions are inflamed over an area of the continental shelf in the Aegean Sea believed to hold rich oil reserves. Territorial waters give the respective state(s) control over shipping. However, foreign ships usually are guaranteed “innocent passage” through those waters. Nevertheless, the Greek military continued a non-stop VHF radio broadcast, warning all vessels from Turkey not to “violate sovereign waters.” Short of heading several hundred miles south toward Egypt, transit through Greek territorial waters would be the only routing option for Flying Fish to sail west.

The passage began with a raging meltemi wind out of the Aegean. Meltemi winds form when a high-pressure system over Greece meets a low-pressure system over Turkey. North winds near gale force are often created in the chute between the two counter-rotating systems. Flying Fish struggled to make forward progress in steep, short-period seas between the islands. Temperatures plummeted as the northerly wind increased. Fortunately, there are abundant sanctuaries for protection from the meltemi among the Greek Islands. I dropped anchor to get some rest in a protected bay at sparsely inhabited Levitha Island, despite the questionable legality of doing so.

At 3 AM, I awoke to the sound of rock meeting fiberglass–never a good sound–and I realized that Flying Fish was not where I had dropped the anchor. In nearly 12,000 miles of sailing since leaving Key West, I had never, until this night, grounded the keel of Flying Fish. As the meltemi roared in the tight anchorage of Levitha, it created a vortex of wind spinning the boat around the anchor and into a rock below the surface. In my state of exhaustion hours earlier, I had made the cardinal error of situational awareness: I did not thoroughly examine my anchorage and allow adequate swing room. Awakened by this startling bump in the night, I sprung out of my berth, started the engine, winched up the anchor, and checked the bilge. There was no water ingress (external inspection would have to wait.) Flying Fish was floating. In pitch-black darkness and violent wind, I reversed my inward GPS track and motored out of the bay to deeper water. Only then I realized that I was half-naked and very, very cold.

“Being from the tropics, I like ice. I’m just not too fond of it when it comes out of the sky.”

By morning there was sleet on the deck of Flying Fish. Temperatures were above 0°C on deck, but freezing rain was falling from the sky. I was still wet from the night’s activity. Being from the tropics, I like ice. I’m just not too fond of it when it comes out of the sky. I needed to find shelter and regroup. The Greek Waters Pilot guide recommends a secure anchorage at Nísos Íos. The book says of the Manganari Bay anchorage: “The island is extremely popular with young sun-lovers. Nude bathing is tolerated here.” A caïque brings beachgoers “topless and bottomless” daily from Íos. But that wasn’t happening today.

News about the blockage of the Suez Canal was scarce over my satellite reports, but I began to see an unending line of merchant ships jamming the shipping lanes toward Port Said. Deciphering lights, radio calls, radar blips, and other electronic information can be like reading code. Why is one ship moving one way while all the others are doing something different? Much of that information transmits by AIS (Automatic Identification System) to my mapping electronics. The AIS tells me who is navigating the same water as Flying Fish, essential information for collision avoidance. Most of the ships noted on AIS were tankers (empty tankers, it turned out, heading to the Middle East for more oil). One vessel was moving much faster than the others. It was listed on AIS as a “Dredging Operator,” expertise much needed considering the current circumstances. The Suez Canal blockage was now a critical event with global economic implications.

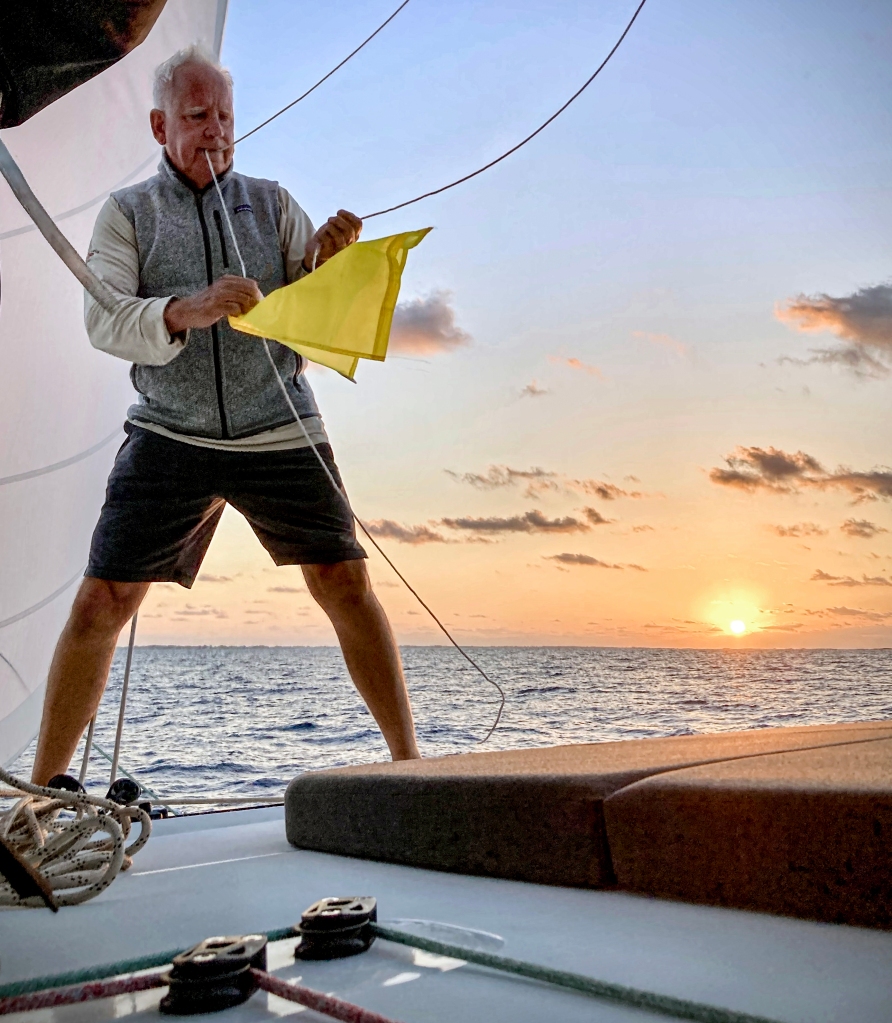

And then–poof!–all of the AIS targets vanished from my navigation screens. Simultaneously, Flying Fish turned abruptly to windward as the autopilot disengaged. Not again! A year earlier, as I began a 3,000-mile passage across the Indian Ocean, Flying Fish experienced an identical system failure. Unable to resolve the problem, I diverted first to Sumatra and afterward to Phuket for repairs (and then came COVID and a circumnavigation interrupted… but that is a different chapter for another day.) Now, 150 miles out of Malta, the situation (it always happens at night) was frustrating but manageable. I would sail the final stretch into the historic Valletta harbor the way my forebears did, using my eyes for navigation and my hands to steer. Even at night, every cloud has a silver lining.

Please click Follow at the bottom of this page so that you don’t miss a new update, and please consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy following the voyage of Flying Fish. I welcome your comments. I will always respond to your comment when I have an Internet connection. And I will never share your personal information.

You can follow the daily progress of Flying Fish, boat speed (or lack thereof), and current weather as I sail into the Mediterranean by clicking this satellite uplink: https://forecast.predictwind.com/tracking/display/Flyingfish. Click the “Legends and Blogs” box on the right side of the tracking page for en route Passage Notes.

To see where Flying Fish has sailed since leaving Key West in 2017, click here: https://cruisersat.net/track/Flying%20Fish

Instagram: FlyingFishSail

Facebook: Jeffrey Cardenas

Text and Photography © Jeffrey Cardenas 2021

Let this be a time of grace and peace in our lives –Fr. John Baker