Eastern Mediterranean to The Cape Verde Islands

“To live is the rarest thing in the world…” -Oscar Wilde

Life aboard Flying Fish in 2021 featured a year of obstacles, astonishment, and kindness.

COVID still raged worldwide, but vaccines kept many people from dying. Generous souls in Malta found a way for me to receive a vaccination from one of the country’s thousands of unused doses, despite a bureaucratic edict prohibiting foreigners from receiving the jab.

As climate change accelerated, storms became more potent. Sahara Desert winds filled the sky with sand. Voyaging sailors banded together, helping one another with repairs and brainstorming solutions for staying safe in the changing conditions at sea.

On shore, despite another year of pandemic and political uncertainty, many people found solace in nature and creativity. On the salon bulkhead of Flying Fish, I kept a crayon drawing by Charlie Vialle, a spirited six-year-old French girl who was sailing the world with her parents. The drawing is of Flying Fish skipping across waves under a bright sun in the company of birds and porpoises. Charlie said, “Flying Fish is a good boat.”

Mid-Winter Departure

Mid-Winter sailing in the Mediterranean is for the (snow) birds

The 2021 sailing itinerary for Flying Fish was ambitious: I would depart the Turkish coastline in the eastern Mediterranean and sail to America. This was the beginning of my fourth year en route around the world, and it was time to think about closing the circle. To accomplish this, I would have to get started early.

The Eastern Mediterranean in January is cold. Temperatures dropped below freezing. On the first leg of the journey from Turkey to Malta, I encountered sleet onboard for the first time in my tropical life. I didn’t like it.

Shipping traffic in the Mediterranean backed up because the massive container ship Ever Given was stuck sideways in the Suez Canal, blocking the passage of 369 ships and causing billions of dollars of world supply chain delays that continue to affect global trade. Flying Fish dodged the traffic and bypassed the lovely Greek Islands, which remained closed to tourism because of COVID.

After 750 miles, Malta was a welcome landfall, but a series of storms known as gregales reminded me that it was still mid-winter in the Mediterranean.

Click a photo in the gallery below and scroll for captions and high-resolution images © Jeffrey Cardenas

Places of Wonder

The engineering feat of Porto Flavia, Sardinia, cut into the sheer rock, made it unique at the time of its construction in 1923

I was continually in a state of wonder at the history surrounding this leg of the passage around the world.

I sailed in the wakes of the ancient Egyptians, Julius Cesar, and Admiral Horatio Nelson. In the Middle Sea, the Hellenic ruins of the Eastern Mediterranean were gradually replaced by surviving relics of the Renaissance and the ascension of Europe. At Malta, 2021 Easter services in the stunning St John’s Cathedral were cancelled because of the pandemic, but a generous security guard opened a side door, allowing me a glimpse of the cathedral’s Baroque grandeur.

I continued to Sardinia from Malta, and welcomed my sailing mate Ginny Stones aboard Flying Fish. We savored the food and wine and the rugged anchorages from Cagliari to the Gulf of Orosei. Ginny’s visit was brief, and after a month, I sailed onward to the Balearic Islands, mainland Spain, Gibraltar, and finally to the Atlantic Ocean islands of the Canaries and Cape Verde.

Click a photo in the gallery below and scroll for captions and high-resolution images © Jeffrey Cardenas

Joyful People

Charlie Vialle, age 6, takes the helm of Flying Fish at Cala Teulera in Menora

From Turkey to the Strait of Gibraltar, the people of the Mediterranean welcomed me as I journeyed into their towns and villages aboard Flying Fish. Despite my vaccination, I still needed COVID tests at every landfall. None was more enjoyable than in Sardinia, where a lovely Italian doctor came aboard Flying Fish and stuck a swab up my nose.

The cafes were full of life, and Ginny found herself surrounded by Italian schoolboys. Three men, all named Mehmet, helped make repairs to Flying Fish in Turkey. I swooned to Flamenco in Grenada, ate fresh tuna hand-caught by Italian fishermen, swayed to a drum circle on a dark beach in Ibiza, and watched a man exercise his swimming horse in the harbor of Marsaxlokk, Malta.

The world was still in the midst of a global pandemic, but you would never know it by the smile in the eyes of the people I met in the Mediterranean.

Click a photo in the gallery below and scroll for captions and high-resolution images © Jeffrey Cardenas

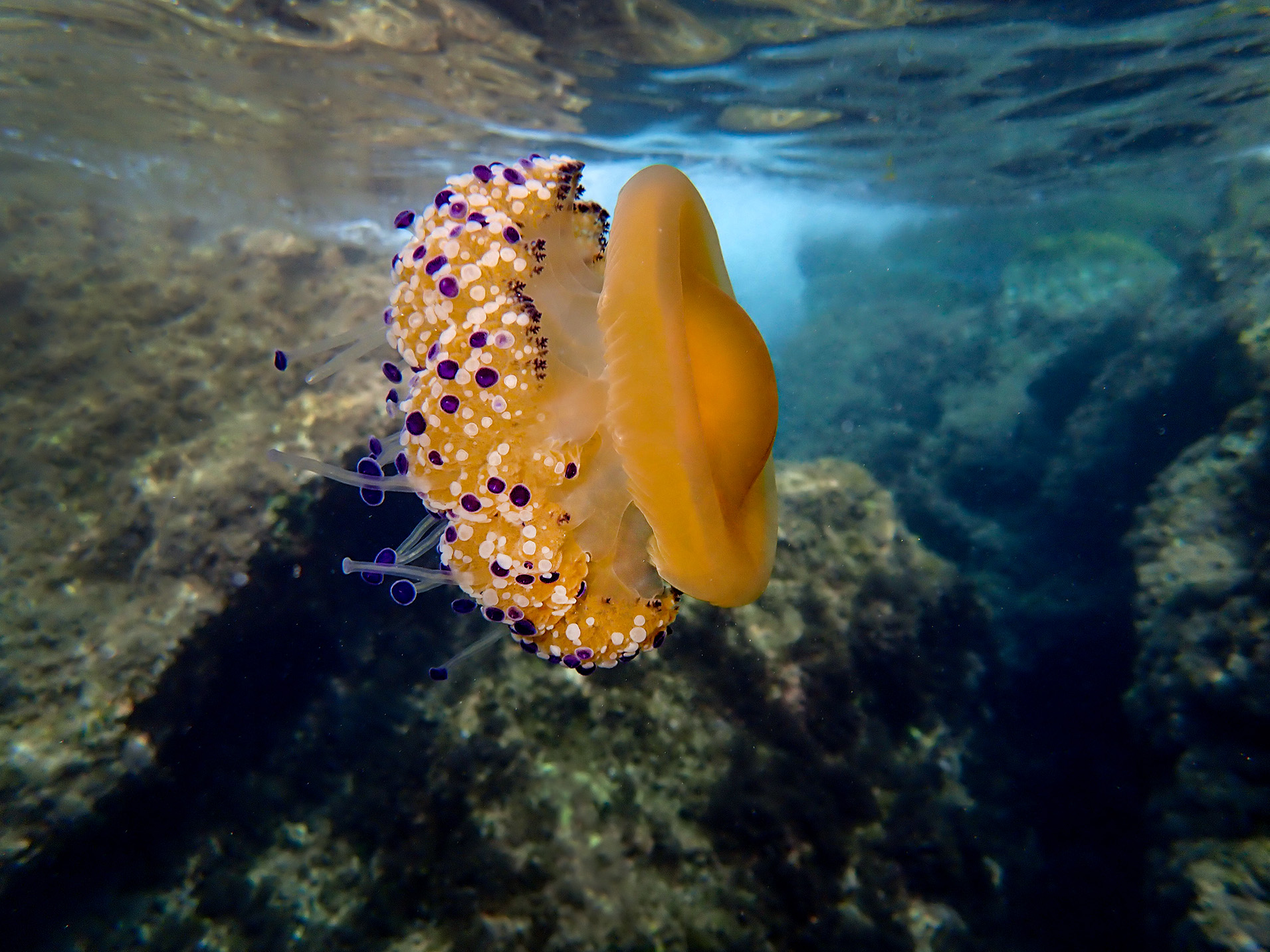

Bizarre Nature

The natural beauty of the Mediterranean is unique in the world.

There are no multicolored coral reefs as in Polynesia. The fish population in the Mediterranean has been feeding people for eons, and in many areas that resource is depleted. There are, however, plenty of two-legged animals (usually wearing thongs in the summertime), especially in the chichi beach resorts of the Mediterranean.

I was more fascinated in searching out the unusual lifeforms. Jellyfish intrigued me. The Fried Egg Jellyfish is being researched for properties to treat cancer patients. I had always loved eating octopus, until I became friendly with these hyper-intelligent creatures living in the Mediterranean. Octopus is no longer on my menu. In Gibraltar, I met the famous “Rock Apes,” macaque monkeys that suffered no fools among the thousands of tourists who visited there. Tease the monkeys with people food, and you are likely to get bitten. In Lanzarote, a volcanic island seemingly without shade, I spent days wandering among the exotic cacti that flourished there.

The basic tenet of nature is adapt or perish. It was a lesson that I would be reminded of during the final passage aboard Flying Fish this year.

Click a photo in the gallery below and scroll for captions and high-resolution images © Jeffrey Cardenas

A Memorable Passage

The year’s final passage aboard Flying Fish was the most memorable.

Ginny again joined me in Gran Canaria for the transatlantic passage to the Caribbean. We fueled and provisioned Flying Fish, and then waited for a perfect weather window to make the 3,000-mile crossing to the Caribbean. I had made this passage before. The Atlantic hurricane season had ended, and the forecast called for a 20-day downwind sleigh ride to Antigua.

What we thought would be an idyllic sail became challenging in unexpected ways. Early on, the mainsail halyard parted, requiring a jury-rigged topping lift to get the sail back up. The weather intensified beyond its forecast, but the good ship Flying Fish is solid, and it handled 30-knot winds with ease. Suddenly, all DC electrical power quit (the result of an uncrimped battery cable, we found out later.) We were sailing traditionally with no autopilot, no navigation, no engine, no electric pumps, no lights, stove, or toilets. The wind increased to gale force near 40 knots. (A sailboat in the ARC Rally departing Gran Canaria at the same time suffered tragedy; a crew member was killed by a boom strike, another was injured, and the remaining crew member abandoned the boat at sea.) Our situation was not life threatening, but it was complicated to manage.

Rather than hand-steer our 22-ton cutter with no navigation except dead reckoning for the remaining three weeks to the Caribbean, Ginny and I decided instead to divert Flying Fish 500 miles to Cape Verde to sort things out. It was a difficult but correct decision.

Here’s the thing about undertaking and overcoming unexpected challenges at sea; the tough part is temporary, and when it is over the resulting feeling (endorphin rush, or whatever) is exhilarating–unlike anything ever experienced. Despite the hardship and disappointment, this memorable passage left me feeling vital, energetic, and present. It made me want more. Remembering the words of Oscar Wilde, I lived in 2021.

###

Click a photo in the gallery below and scroll for captions and high-resolution images © Jeffrey Cardenas

Flying Fish is being refitted in Cape Verde and will resume its passage toward Key West early in 2022.

As always, Sailing is not just about the wind and the sea; equally important are the places where Flying Fish carries me, and the flora, fauna, and people I encounter along the way.

Please click “Follow” at the bottom of this page so that you don’t miss a new update,- and please consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy following the voyage of Flying Fish. I welcome your comments, and I will always respond when I have an Internet connection. I will never share your personal information.

You can follow the daily progress of Flying Fish, boat speed (or lack thereof), and current weather as I sail into the Atlantic by clicking this satellite uplink: https://forecast.predictwind.com/tracking/display/Flyingfish. A Bonus: Click the “Legends and Blogs” box on the right side of the tracking page for passage notes while I am sailing offshore.

To see where Flying Fish has sailed since leaving Key West in 2017, click here: https://cruisersat.net/track/Flying%20Fish.

Instagram: FlyingFishSail

Facebook: Jeffrey Cardenas

Text and Photography © Jeffrey Cardenas 2021

Let this be a time of grace and peace in our lives – Fr. John Baker