It is becoming more difficult these days to determine what is a truly wild experience. I am thinking about this after a day swimming among sea turtles in the Exuma Islands.

The Navionics charts aboard Flying Fish have a notation that indicates a nearby bay known for its population of green turtles. I love turtles, wild sea turtles. (I am unsettled when I see them on display in enclosures). So, without delay, I grab a mask and snorkel, my underwater cameras, and navigate up the Exuma island chain in my dinghy to find the green turtles.

They find me instead.

Moments after I flip over the side of my little rubber boat, I feel something close its mouth on my upper thigh. It’s nothing dramatic; just a little nip and it lets go. When my mask clears, I see that the nip came from a green turtle the size of a garbage can lid. Adult green turtles only eat grass. Perhaps this one thinks taking a little taste of my ham hock will get my attention. It does.

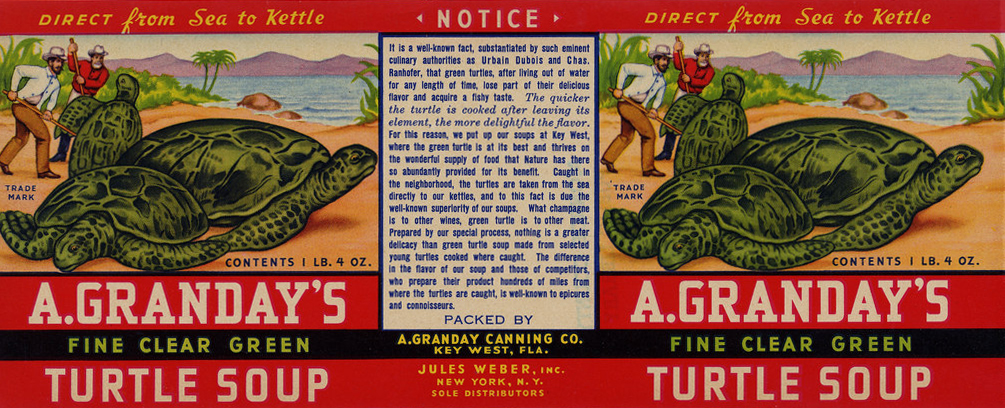

Unlike a mature green turtle, I’m not vegan. I love seafood. I have memories as a kid eating green turtle steaks in the old Compleat Angler Inn at Bimini (before it burned down during the drug years). Many years before that, Key West also had a thriving green turtle trade. The A. Granday Canning Co, manufactured Fine Clear Green Turtle Soup in Key West in 1930 and claimed that its turtle meat came from the waters around the Florida Keys. “Caught in the neighborhood,” the marketing said, but by the 1930s the green turtle population “in the neighborhood” was already diminished and the turtles arrived in Key West on schooners, captured primarily in the nets of turtle hunters from the Cayman Islands.1

Turtles were easy targets to net or spear, and their eggs–sometimes 100 in each clutch–were stripped from beachside nests. By the middle of the 20th century, the green turtle population worldwide had crashed.

With the passing of the 1973 Endangered Species Act, the US joined international conservation efforts to stop the trade in endangered species, including green turtles. (In the Bahamas, it took another 36 years before the harvesting of green turtles was finally outlawed.) The population of green turtles rebounded. There were fewer than 300 nests in 1989 at 27 of the main beaches in Florida where the animals come to lay eggs. In 2019, that number reached 41,000.2

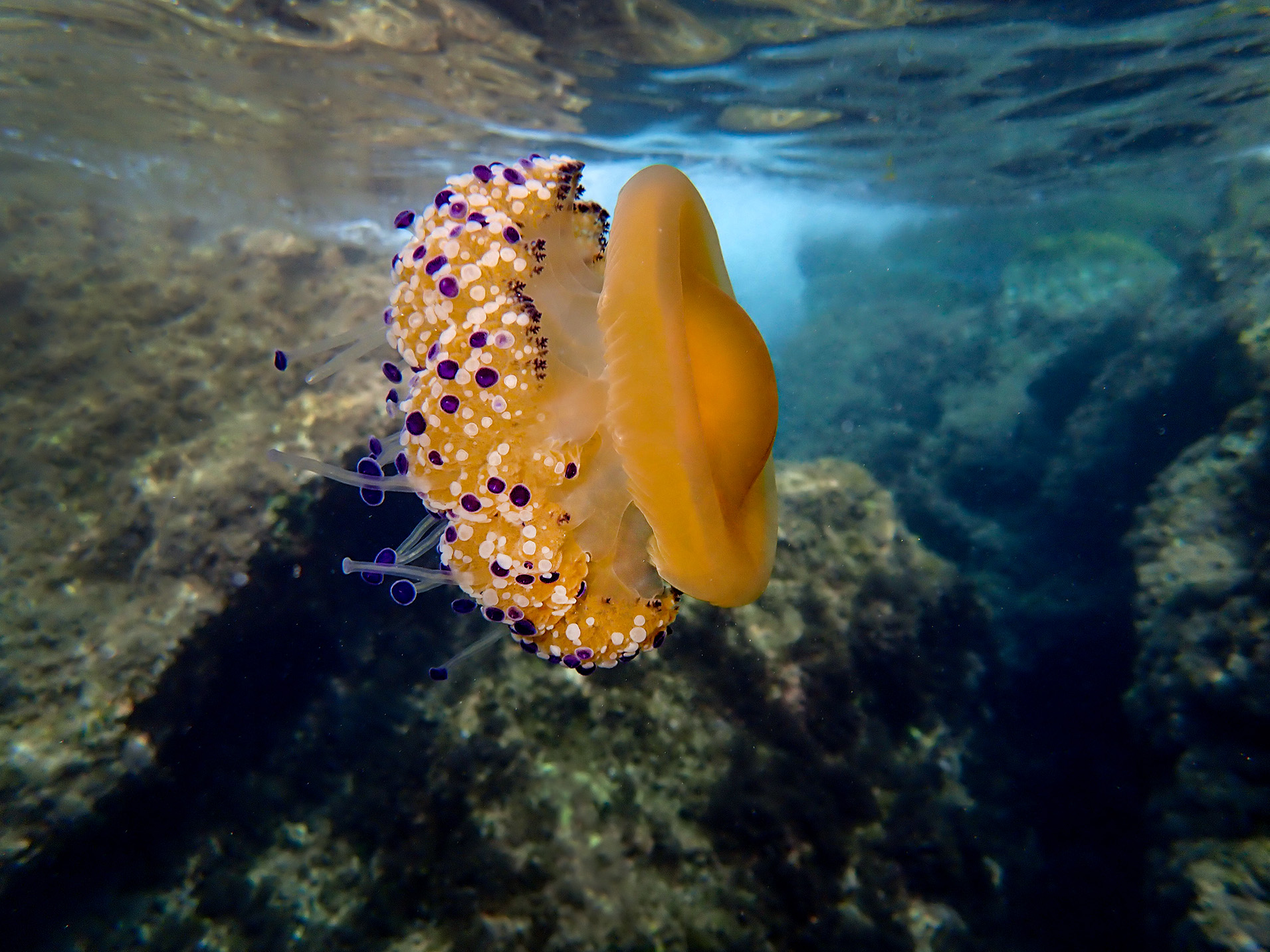

For a couple of hours, I snorkel alone with the green turtles. This particular bay is not a part of the Exuma Land and Sea Park. There are a few homes and docks here, but the water is clean and clear. Mature turtles spend most of their time in shallow, coastal waters like these with lush seagrass beds. The turtles here are unthreatened by my presence. In fact, they swim directly toward me and nudge my camera. They are fearless in their curiosity, making eye contact with me, occasionally rising to the surface for a breath, and then lowering their heads to see if I am still there. I hover motionless as at least 10 different individuals come calling. I resist an overwhelming temptation to reach out and touch them. Most of the turtles are in perfect physical condition, although some have scratches and wear marks on their carapaces, and one has a scalloped bite mark deforming its shell. Tiger sharks are the only creature, other than man, known to eat green turtles.

I am surrounded by turtles as I float in this wonderland. But what is it that makes them so tolerant of my presence? And why are they here and not in other places?

Then, the first tour boat arrives in the bay. Two more follow, and I have the answer to both questions. The boats are filled to capacity with tourists holding bottles of Kalik beer and gyrating to onboard hip hop music so loud that I can hear it underwater. The guides on these boats have plastic bags of lettuce and squid parts that they fling like confetti into the water. The green turtles suddenly leave me as if I am toxic. They swarm around the tour boats instead. It’s a party to which I suddenly feel uninvited.

I quickly realize that the turtles were not hovering around me because they thought I was interesting; they thought that I was going to feed them. What seemed to me to be a wild experience was nothing more than being in the presence of once-wild animals that have now been conditioned by human behavior to beg for food. It’s like seeing brown pelicans waiting for handouts at a fish cleaning table. Or, tarpon being fed processed food pellets at a marina dock. These creatures do not need to eat handouts… until, of course, the day comes when these creatures forget how to forage in the wild.

Unknown to me until now, there has been much published about feeding Exuma’s green turtles. And it doesn’t happen only in the Bahamas. Human interaction with sea turtles is big business wherever turtles thrive. In Exuma, the island industry bills itself as Eco-Tourism. “Come experience wild sea turtles in their natural environment,” one company advertises. The website Exuma Online writes: “The local sea turtles are a must see. Where else can you swim so close to these wild animals? (my italics).

“Keep your fingers in check,” the tourist website continues, “bring some squid, and get ready to take some amazing photos! Just be sure that you respect these animals and the surrounding environment.”3

Could anything be less respectful of these “wild animals?” Green turtles don’t even eat squid in the wild4 –they’re herbivores–but these “Eco-Tourism” turtles have been conditioned to eat this bait like there’s no tomorrow. And for some of them, there may be no tomorrow.

Dutch scientists of Wageningen University & Research used Turtle Cams5 to see how ecotourism affects green turtles in the Bahamas. The cameras were mounted on the shells of five turtles and disconnected automatically after five hours. The footage shows people in the water feeding the turtles, and the frenzy that ensues. There is aggression and biting among the turtles (which may explain the turtle nip on my backside). Green turtles are seen in the video dodging the thrashing arms and legs of squealing tourists as they battle each other for squid and floating lettuce.

I understand that for some people this may be the only way they will ever have a close encounter with a sea turtle. But does that make it right to participate in changing the diet and behavior of these animals? There may not be any fences or walls in this bay, but these hand-fed green turtles are no different than those that are captive in zoos or aquariums.

As I drift away from the hip-hop Eco Tourism boats, I see a solo green turtle has also eased away from the melee. I keep my distance, and for 30 minutes I slowly follow it into the bay. This is odd, I think. Is this turtle healthy? Why isn’t it behaving like the other squid-and-lettuce junkies? It is clearly aware of my presence, but the turtle ignores me. Then it sinks down to the sea bottom. Oh God, I think, please don’t let it die right here!

Instead, the green turtle extends its neck, opens its finely serrated jaws, and takes in a mouthful of grass. Turtlegrass. This lone green turtle chews with what I interpret as a look of contemplation and satisfaction. Suddenly, all seems right in the natural world.

Resources:

1 Image credit: Monroe County Public Library of the Florida Keys

2 Index Nesting Beach Survey Totals 1989-2021–Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

3 7 Recommendations For Swimming With Sea Turtles–Exuma Online

4 Green Turtles–World Wildlife Fund, WWF.org

5 Caught on film! TurtleCams show how tourists feed (and influence) turtles–Wageningen University & Research

Thanks for sailing along with Flying Fish.

As always, Sailing is not just about the wind and the sea; equally important are the places, the flora, fauna, and people encountered along the way.

Please click “Follow” at the bottom of this page so that you don’t miss a new update,- and please consider sharing this post with others who might enjoy following the voyage of Flying Fish. I welcome your comments, and I will always respond when I have an Internet connection. I will never share your personal information.

You can follow the daily progress of Flying Fish, boat speed (or lack thereof), and current weather as we sail into the Atlantic by clicking this satellite uplink: https://forecast.predictwind.com/tracking/display/Flyingfish.

To see where Flying Fish has sailed since leaving Key West in 2017, click here: https://cruisersat.net/track/Flying%20Fish.

Instagram: FlyingFishSail

Facebook: Jeffrey Cardenas

Text and Photography © Jeffrey Cardenas 2022

Let this be a time of grace and peace in our lives – Fr. John Baker